Dangers of Semantics within the National Security Orbit

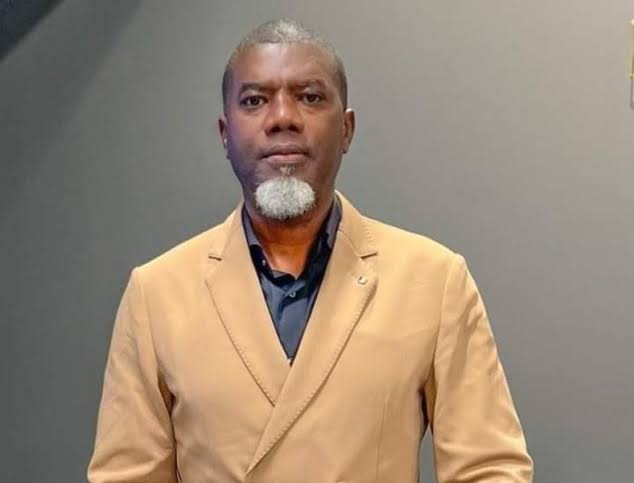

By Oseloka H. Obaze

To insiders, the proverbial glass is neither hardly ever half full nor half empty. Insiders, who also know where the proverbial corpses are buried, can always tell if a glass was half-filled, or full, and drank down to half.

Join our WhatsApp ChannelIn our present national circumstances, only outsiders who are not within the realm and orbit of critical decision-making would presume a glass to be half full or half empty, more so in moments of heady decision making pertaining to national security issues confronting Nigeria.

There are inherent dangers in deploying expedient semantics into national security matters. For national security policies to be efficacious, the situations, issues, actors, scenarios, assessments and decisions must each be explicitly characterized; and those characterizations, must be commonly shared, without any ambiguities. Failure to do so has dire consequences. Consequently, lack of clarity in the identification, definition and assessment of prevalent challenges, risks eliciting inadequate or wrong policy responses.

This is a risk presently comforting Nigeria. History can be instructive. In 1991, Iraq invaded Kuwait, months after an American envoy, reportedly offered a politically correct, but offer-hand response to Saddam Hussein that was laden with semantic ambiguity. The consequences were dire, for Kuwait and for Iraq.

Whereas diplomats can and do have the professional prerogative of deploying obfuscating words when conveying variants of messages; in tactical, intelligence, military and security matters, wordings and language pertaining to policies, command, control and communication, has to be clear, precise, unfettered and disambiguated.

There is clear and present danger inherent in the ensuing controversy over the semantics on the prevailing insecurity in Nigeria, and whether the conduct, actions and results of the ongoing visceral violence, bloodletting and killings, are tantamount to genocide or not.

Genocide has very clear definition, global examples and thresholds. Genocide is not a one-off event, but a progressive gruesome pogrom that manifests fully, if left unchecked. By definition, “Genocide is the deliberate, systematic destruction of an ethnic, racial, religious, or national group.” And here is the crux of the issue; has Nigeria reached the applicable threshold? Are the globally applicable benchmarks for determining genocide, now prevalent in Nigeria?

Put in its proper context, Raphael Lemkin, the coiner of that terminology, did state that “genocide does not necessarily mean the immediate destruction of a nation. It is intended rather to signify a coordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves.” Coordinated plan. Different actions. Destruction of essential foundations. Aim of annihilating groups. These are critical component of the genocide mosaic. Horrible things happen when a series of small unchecked actions converge.

In 1948, by virtue of the U.N. Genocide Convention, any form of linguistic ambiguities arising from semantics, was removed, and the legal definitional basis of measuring acts of genocide was expanded to include, “acts like killing, causing serious harm, imposing conditions of life that lead to destruction, preventing births, and forcibly transferring children of the group.” The common variables of genocide are the perpetrators, the intent, the act, and the victims.

Nigerians are acutely aware that numerous Nigerians have been and are still being killed. Most are targeted and killed as a collective: in their farms, homesteads, communities or in their churches. Nigerians know also of the pervasive insecurity nationwide, as well as killings arising from herders-farmers conflict, and those from Boko Haram insurgency. Above all, Nigerians know of the rise in banditry, the ungoverned spaces, and undoubtedly, the fact that indigenous communities were being sacked and Christian churches were being razed, and their congregations brazenly killed in cold bold. Names of communities like Owo, Basa, Oturkpo, Akpanta, Guma, Yelunta, Wanunne, Gwoza, Tsafe, Giedam and Mangu, gradually crept into the national consciousness and lexicon, as places where massacres took place. These were places and silos where genocidal acts might have been committed.

Across the nation, the number of killings has risen progressively. And beyond doubt, the key variables remain ever present in every instance: the intent, the act, the victims, and the perpetrators. Because the perpetrators were extremist groups, notably Boko Haram and the Islamic State in West Africa Province (ISWAP), it matters little, if you term their activities Jihadist or Genocide. The enormity and consistency of the killings cannot be ignored or diluted by labels and definitions. In 2024, well over 2,194 people were killed by Fulani armed bandits. In the first quarter of 2025 alone, 2,266 people were killed. These represent a high fraction of the over 600,000 deaths arising from insecurity nationwide between 2024 and first half of 2025.

The irony was and remains that those who obliquely and conveniently favoured or tacitly deferred to a jihadist intent and mission, were mute as their compatriots were being slaughtered. Once the acts were characterized as genocide, the same people turned defensive promptly. As it turned out, the nation itself was in utter denial, more so, the leadership and the ruling APC government. It took U.S. President Donald Trump to utter the defining G-word on 31 October, 2025 and declare Nigeria a “Country of Particular Concern” for the national leadership to awake from its pathetic slumber.

Those who have argued that in Nigeria, Christian and Muslims alike were being killed may have a point, insofar as those killings were those resulting from farmers-herders and other resource-control induced conflicts. But the ISWAP bandits and Fulani jihadists were and are still on a well-defined mission of annihilation. We cannot gloss over this reality. Their audacity, scope, capacity, resources, are also indicative of broad internal or external support. Nigeria’s combined national security apparatus seems by design or default, utterly incapable of interdicting and containing the bandits. As internal compromises are made, and infiltration becomes rife, Nigerian soldiers are being mercilessly slaughtered. The fate of defenseless civilians is even more precarious and dire.

Tinubu Needs Strong Executives Not Cronies, Minions To Implement Oronsaye Report – Obaze

Besides the annihilation tendencies, when entire communities are sacked, their homesteads are frequently occupied and their natural resources coveted by the bandits and their paymasters. So, if the goal is not genocide, then it must be economic and the appropriation of rare earth minerals domiciled in the environs of the sacked communities. Either way, Nigeria is at grave risk.

While the inherent dangers of semantics in the national security orbit persists, secular Nigeria, certainly, does not want to join the ranks of nations only remembered for being places where unfettered massacres took place and acts of genocide were perpetrated. The trajectory to that dubious distinction, which is already afoot, starts with willful governmental indifference, denial and inaction.

Historically, there are striking similarities between the emergence of Fulani bandits in Nigeria and the emergence of the Al-Shabaab militia in Somalia and the Janjaweed militia in Sudan. We know where Somalia and Sudan have been as war torn nations. We need not toe that path.

Nigeria is already a very polarized nation at war with itself. Early warnings are indicative. So, whether the ongoing killings in Nigeria are sufficiently sectarian to qualify as jihad, genocide or not, is immaterial. This is not the time for our leaders to be apologetic or to deploy exculpatory semantics. Given Nigeria’s diversity, the dismembering of any ethnicity, religion, or indigenous community is not a circus. Put plainly, here is the inconvenient truth. There is an unfolding dissembling process in Nigeria. These killings represent a precursor to more entrenched mayhem if left unchecked. If these acts seem, smell, sound, feel, or are coloured like genocide, then the process must be stopped before it is concretized, and Nigeria arrives a point of no return, where it will be confirmed that acts of genocide were indeed perpetrated, even if in silos.

Deploying semantics, apologies and negotiations as rationalizing ploys or policies is starkly defeatist. We are at war with the bandits. Let’s fight that war in a full frontal manner or risk being consumed. Rule of law and the responsibility to protect Nigerians, compel immediate action, not apologia. A stitch in time saves nine.

———-

Obaze is MD/CEO, Selonnes Consult – a policy, governance and management consulting firm in Awka.

- Editor

- Editor

- Editor

- Editor

- Editor