The main fears and warnings of critics of the actions of Anambra governor, Professor Chukwuma Soludo about sit-at-home and closure of the Onitsha Main Market have now happened.

In Anambra, fear and panic came back in full measure, while the State Police Command, through it public relations officer, Tochukwu Ikenga, blamed social media for spreading panic.

Across the Southeast of Nigeria, schools that had begun Monday sessions are in danger of backtracking. Thanks to Soludo and waking sleeping dogs. The question remains: who are the real troublers of the peace in Southeast Nigeria?

Join our WhatsApp ChannelMoreover, Governor Chukwuma Soludo’s recent meeting with leaders of the Onitsha Main Market has produced a proposal for a phased remodelling and redesign of the market, framed as modernization, orderliness, and economic revival.

On paper, the language is attractive: reclaimed walkways, colour-coded shops, improved sanitation, and a master plan prepared by experts. In practice, however, traders must pause and interrogate not just the design, but the political and regional context in which it is being offered.

Across the Southeast today, there is growing evidence that grand redevelopment schemes often end in displacement, economic loss, and unanswered questions.

READ ALSO: Sit-at-Home, Markets, and the Politics of Economic Punishment in Anambra

This is why the central warning must be stated plainly: no trader should accept a plan that takes everything out of the market without a concrete, enforceable alternative already in place. Recent experiences show that once businesses are uprooted, promises thin out, timelines stretch, and livelihoods quietly disappear.

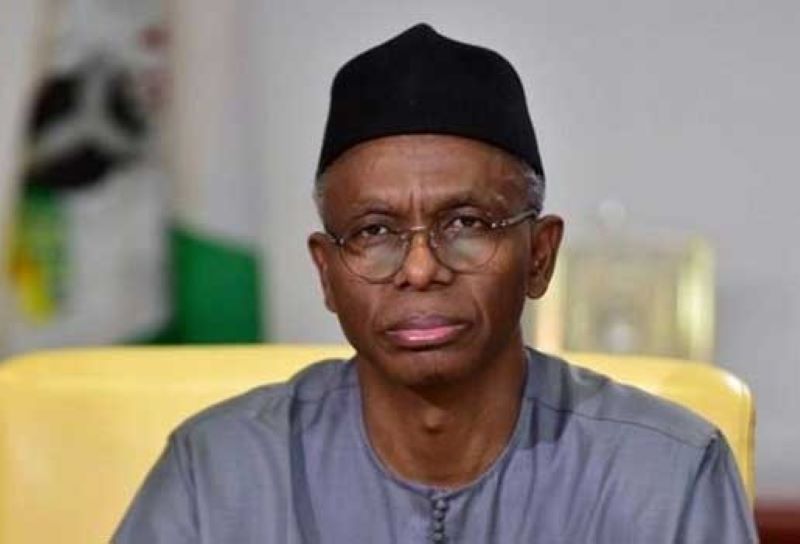

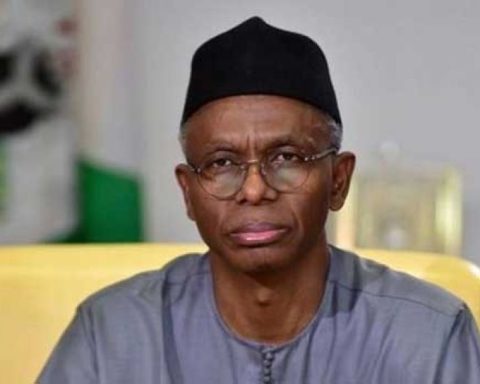

Soludo and the Dangerous Echo of Conspiracy

It is no longer alarmist to say that several Southeast governors have given citizens cause for suspicion. Only recently, Governor Soludo inadvertently lent oxygen to a dangerous conspiracy narrative, i.e., that Southeast governors may be instruments in a broader scheme to economically weaken the region. Whether he intended this or not, it vibrates because patterns on the ground seem to support economic disruption rather than empowerment.

READ ALSO: Sit-at-Home, Markets, and the Politics of Economic Punishment in Anambra

The fear therefore is that threats of market closure may be a grand design to remove traders from the market in order to pull it down in line with new market proposals. This fear remains unfounded though given the options laid out by the governor to the traders, which include phased remodelling to avoid disrupting business activities. But there is still room for caution.

Development is increasingly defined by demolition and prestige projects, not by livelihood protection or social welfare. In Enugu State, for example, at least four major markets were damaged or dismantled by Governor Peter Mbah under redevelopment exercises. What replaced them were far fewer stalls than the number destroyed, alongside projects such as fuel stations in a state where fuel outlets are already ubiquitous. Thousands of traders were displaced, with some reported dead due to shock.

More troubling is the over 40-kilometre stretch of demolitions between Abakpa (Enugu city) and Opi (Nsukka). Homes, shops, and small businesses were pulled down to make way for a dual carriageway that is essentially a diversion from the long-abandoned Opi–Ninth Mile federal highway. After the destruction, the final road alignment reportedly does not come within three metres of many of the demolished buildings, not even accounting for pedestrian walkways or drainage gutters. Some of the affected structures reportedly had planning approvals. Even if not, no public official has been sanctioned for permitting their construction in the first place. The question remains unanswered: why punish citizens while protecting institutional negligence?

Beyond urban centres, farmlands in Unadu (Igbo-Eze South LGA) and Obimo (Nsukka axis) have been cleared for market layouts or export-crop ambitions, displacing subsistence and commercial farmers alike. In a region where agriculture remains a shock absorber against unemployment and inflation, this represents a direct assault on food security and rural livelihoods.

The Enugu State Government’s proposal to ban tricycles (keke) and minibuses from designated metropolitan routes further deepens anxiety. Tricycles are transport devices as well as employment platforms for thousands, including (post) graduates who have been locked out of formal employment. No credible data has been published showing how many will be absorbed into alternative jobs, or when.

White Elephants across the Southeast

This anxiety is not confined to Enugu. In Abia, Ebonyi, and Imo States, billions of naira have gone into flyovers, airports, aircraft purchases, and prestige infrastructure, even as public schools decay, hospitals lack equipment, potable water remains scarce, and rural roads are barely motorable.

Some commentators, including economists, civil engineers, and community leaders, have repeatedly described these projects as white elephants: airports with few commercial flights, flyovers that are more of political city markers than facilitators of transport, and aircraft acquisitions in states struggling to pay salaries and pensions. The criticism is consistent: visibility has replaced viability.

Onitsha Traders Must Demand a Grand, Binding Alternative

Onitsha Main Market is a huge trading space. It is one of West Africa’s largest commercial ecosystems, supporting tens of thousands of direct and indirect jobs. Any redesign that requires traders to vacate, even temporarily, must come with a fully developed, accessible, affordable, and legally guaranteed alternative market space before the first structure is touched.

The odds, based on regional experience, favour displacement without return. Traders must therefore ask: Where exactly will businesses relocate, including names, locations, layouts? How many stalls will be provided compared to existing numbers? What legal guarantees ensure reallocation after redevelopment? Who bears losses during transition?

The governor’s hardline approach to Monday market closures also raises concern. The sit-at-home culture was already quietly receding in Awka and other areas, as the governor himself has acknowledged. Why escalate through shutdowns and threats instead of persuasion, incentives, and economic reassurance? History shows that coercion often reawakens sleeping dogs.

There Are More Urgent Needs

If Governor Soludo seeks transformative legacy projects, Anambra’s needs are well known: A functional seaport and dredging of the River Niger to unlock regional trade; rural road rehabilitation to connect farmers to markets; potable water schemes and steady power supply, business support through loans, training, and insurance. Markets flourish when governments enable, not uproot.

Onitsha traders must remember this hard lesson from the Southeast’s recent past: once your business is removed in the name of modernization, recovery is no longer guaranteed. Development that empties markets without safeguarding livelihoods is not progress. It is erasure.

- Editor

- Editor

- Editor

- Editor

- Editor