At the death of Desmond Tutu, December 26, the roll call of the history of his religious service became for many the only real grasp of his religious life. Before now, many glossed over his archbishop title as a mere nomenclatural appendage rather than as a precursor to a fulfilled religious vocation.

Reason? Tutu, 90, lived for far more than a ‘normal’ religious vocation, and here lies the lesson he taught with his 36-year spell as a foremost Anglican cleric. This may be the cause of the lamentation of President Cyril Ramaphosa, who cried that Tutu’s death marked “another chapter of bereavement in our nation’s farewell to a generation of outstanding South Africans” who fought for “a liberated South Africa.”

Looking at Tutu’s brand of religion, one can only show apprehension about the brand of religious service in today’s Nigeria for which many now blame religion for Africa’s underdevelopment.

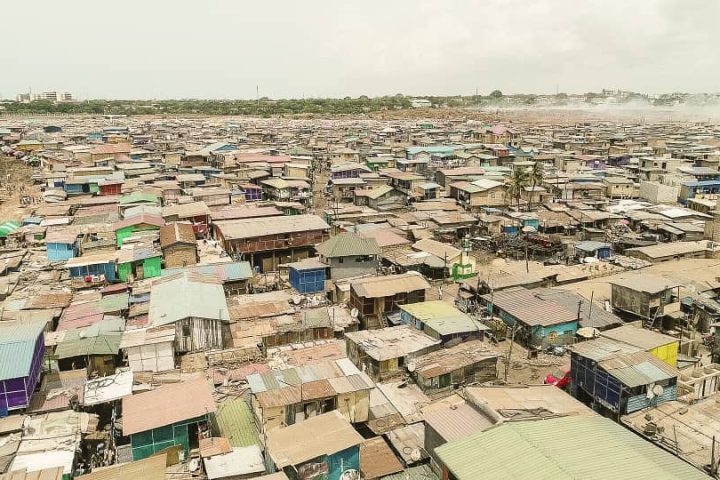

Join our WhatsApp ChannelWith over 20 million of the 70 million labour-force ready Nigerians unemployed or underemployed, religion has quickly become a source of succor and employment to many, who manipulate the vulnerable.

Our own brand of religion has therefore become more of symptoms of a dire socio-economic malaise, and we need other Tutus to challenge the anomaly. The archbishop’s life showed that religion can rather be the solution.

Across Africa, particularly in Nigeria, we have many clerics of the Islamic and Christian faiths who see their vocation from various perspectives. Many live and die around the pulpit, calling people to repentance, but rarely ever confronting the bad eggs, including those who commit crimes right in the place of worship. On the contrary, many Nigerians have berated some clerics such as Rev. Fr Ejike Mbaka of the Enugu Diocese and Bishop Hassan Kukah of Sokoto diocese for just speaking out against what they saw as bad governance and rampant insecurity.

We have heard severally calls from many quarters asking clerics to focus on their vocation of pulpit religion rather than meddling into politics. Beyond pulpit criticism, Archbishop Desmond Tutu plunged headlong into social activism, championing the rights of the underprivileged and physically brawling with the authorities.

Rather than only so-called power packed crusades, miracle extravaganza and deliverance nights, we also need civil rights crusades, anti-terrorism advocacy, rehabilitation for repentant bandits, joint fundraising to repair local roads, build industry, support businesses and victims of conflicts.

We do not speak about one-off charities during emergencies, but strategic multi-denominational and cross-religious crusade to hold leaders to account.

We can today sing about Tutu’s Nobel Peace Prize, his writings, ideology, calm demeanor and wide acclaim. We should also remember that he was well-known to criticism, dangerous anti-apartheid trips around the world, reprimands, passport confiscations, prison terms, hate mail, threats to life, fines, etc.

He was undaunted when his contemporaries despaired, insisting, as he did after a prison stint in 1980, that “Moses went to Pharaoh repeatedly to secure the release of the Israelites.”

We need this type of religion more, not those who are in it for private profits and political correctness. We need to salvage religion from its current misuse; the bogus miracles, rituals, beauty pageantry and bloodletting.

Tutu has shown the real import of religious service; the tangible balance and the direct connection between spiritual worship and temporal life. None should negate the other. As President Ramaphosa rightly observed: Tutu was “an iconic spiritual leader, anti-apartheid activist and global human rights campaigner”, “a patriot without equal; a leader of principle and pragmatism who gave meaning to the biblical insight that faith without works is dead.

Tutu tried to fuse Christian theology into African worldview for which the apartheid system in Africa was never going to be acceptable. The same Bible and Koran that asks religious adherents to be obedient to leaders also asked the leaders to be considerate, seeking the interest of their subjects.

Where neither the followers nor the leaders pay heed to these principles, men like Tutu cried foul. He was well-known about transforming non-violent means into lethal weapons to match the brute force of the apartheid system.

This almost brought him criticism for supporting armed freedom fighters, but he was quick to explain the temptation to violence when leaders leverage legitimate social institutions to oppress minorities and majorities.

Pastors should not accept religious posts for self-aggrandizement. They should be seen to defend religious faith and human rights. Many of the problems of religion in Africa are symptoms of a failing system more than the cause.

That said, the followership enjoyed by many religious leaders is a powerful standpoint for society to forge a common front for social progress by calling the leaders to account. Religious leaders can as well provide revolutionary leadership like Archbishop Desmond Tutu.

Dr Marcel Mbamalu is a Development Journalism expert and Publisher/Editor-in-Chief of Prime Business Africa

A Good read. It’s Informative, thank you DR!

Nice write up Dr Marcel. I totally agree with your lines of reasoning.