On October 7, 1967, one of the most tragic events of the Nigerian Civil War unfolded in Asaba, present-day Delta State. Federal troops entered the town and opened fire on hundreds of unarmed civilians, leaving a trail of destruction that has remained one of the most painful memories of that conflict.

Fifty-eight years later, Asaba still bears the emotional weight of that day, remembered by historians as a symbol of the war’s toll on civilians.

The War Context

The Nigerian Civil War, also known as the Biafran War, broke out in July 1967 following the Eastern Region’s declaration of independence under Lt. Col. Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu. The war was marked by severe fighting, humanitarian crises, and widespread displacement across the country.

Join our WhatsApp ChannelAsaba, situated on the western bank of the River Niger, became strategically significant because of its proximity to Onitsha, a major city under Biafran control. When federal forces from the 2nd Division, led by Col. Murtala Mohammed, advanced through the Midwest region toward Onitsha, Asaba lay directly in their path.

Prelude to the Massacre

In early October 1967, federal troops entered Asaba after fierce battles with retreating Biafran forces. Reports from witnesses and later academic studies suggest that the soldiers, angered by the losses they suffered in nearby engagements, accused Asaba residents largely Igbo-speaking of supporting the secessionists.

Accounts describe how soldiers began house-to-house searches, leading to arbitrary arrests, shootings, and destruction of property. The violence escalated rapidly, setting the stage for what would later be known as the Asaba Massacre.

The Events of October 7, 1967

Community elders in Asaba sought to end the violence by organizing a peace rally. Men, women, and children came out dressed in akwa ocha, the traditional white attire symbolizing peace, chanting “One Nigeria!” to demonstrate loyalty to the federal cause.

Eyewitnesses say the troops initially appeared receptive but soon ordered the crowd to assemble at Ogbe-Osowa Square. There, soldiers separated the men from the women and opened fire.

The number of victims remains uncertain. Early reports put the toll in the hundreds, while some local accounts claim that more than 2,000 civilians mostly men and boys were killed over several days. Survivors say the women were forced to bury the dead in mass graves.

The violence continued beyond the square, spreading to nearby locations such as John Holt premises, St. Patrick’s College, and Umuajia, extending into early 1968.

READ ALSO: Uzodimma Inaugurates Imo State Boundary Committee, Urges Peaceful Resolution Of Disputes

Nigeria, Brazil Seal Landmark Deals as Air Peace to Launch Lagos–São Paulo Flights

Accounts and Alleged Command Responsibility

Several historical sources and oral testimonies have attempted to identify those responsible. Some accounts attribute the killings to troops acting under the 2nd Division’s command structure, allegedly on the orders of Col. Ibrahim Taiwo, then a senior officer under Col. Murtala Mohammed.

One survivor, Dr. Uchenna Gwam, who narrowly escaped the shootings, later said the soldiers appeared to believe that Asaba men were related to Major Chukwuma Patrick Nzeogwu, nicknamed Kaduna the officer who led Nigeria’s first military coup in 1966. This perception, he said, may have contributed to the soldiers’ hostility.

However, there has been no official inquiry or confirmation of individual responsibility, and the massacre remains one of the least investigated episodes of the war.

Aftermath and Legacy

By the end of October 1967, Asaba was almost deserted. Many families had lost multiple generations of men; homes were looted or destroyed. For decades, survivors lived with the trauma in silence, as the country moved on from the war.

Scholars such as Prof. S. Elizabeth Bird and Fraser Ottanelli later documented the massacre extensively in their book, The Asaba Massacre: Trauma, Memory, and the Nigerian Civil War (2017), drawing on eyewitness interviews and archival materials.

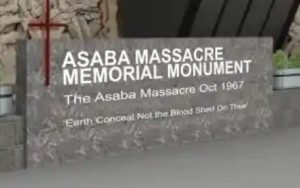

In the same year, marking fifty years since the killings, the Asaba Memorial Arch was inaugurated as a cenotaph to honour the victims, with hundreds of names inscribed in remembrance.

Remembering Without Anger

Today, Asaba is a thriving capital city, but the memory of 1967 remains part of its historical identity. Each year, quiet remembrance ceremonies are held at the memorial site. Survivors and descendants reflect not only on the loss but on the lessons of war and reconciliation.

No official apology or government investigation has been issued to date. Yet, among the people of Asaba, remembrance endures not as a call for vengeance, but as a reminder of the human cost of conflict and the need for peace in a country still navigating its divisions.

A Painful Lesson in History

Fifty-eight years after the guns fell silent, the Asaba Massacre remains a stark illustration of how civilian populations often pay the highest price in times of war.

For historians, it stands as both a warning and a lesson that reconciliation is incomplete without remembrance, and that the stories of those who perished must continue to be told, not to reopen wounds, but to preserve truth.

Amanze Chinonye is a Staff Correspondent at Prime Business Africa, a rising star in the literary world, weaving captivating stories that transport readers to the vibrant landscapes of Nigeria and the rest of Africa. With a unique voice that blends with the newspaper's tradition and style, Chinonye's writing is a masterful exploration of the human condition, delving into themes of identity, culture, and social justice. Through her words, Chinonye paints vivid portraits of everyday African life, from the bustling markets of Nigeria's Lagos to the quiet villages of South Africa's countryside . With a keen eye for detail and a deep understanding of the complexities of Nigerian society, Chinonye's writing is both a testament to the country's rich cultural heritage and a powerful call to action for a brighter future. As a writer, Chinonye is a true storyteller, using her dexterity to educate, inspire, and uplift readers around the world.