WORLD leaders on July 28 and 29 met in the United Kingdom for a Summit on Financing Global Partnership for Education (GPE 2021-2025).

The meeting seeks to raise $5 billion in five years to finance formal schooling in 90 countries, where 80% of out-of-school children live.

Join our WhatsApp ChannelThe summit, which attracts heads of state and governments, officials and youth leaders aims to transform education through exchange of best practices. It encourages member countries to do just more than local education funding by emphasising learning outcomes and adopting new, result-oriented methods for students.

While Nigeria’s President Muhammadu Buhari was in London for this event, the subnational government of Kwara State, led by Governor AbdulRahman AbdulRazaq, was putting finishing touches to a local education conference, which eventually held August 5.

It perfectly summarized Africa’s education problems and progress that must be made. Clearly, the governor noted that education had come through years of blacklist and “near collapse state.”

PHOTO; UNICEF

Among the issues he raised as areas where huge gaps exist are out-of-school children, poor state of technical and vocational education and training (TVET), low educational budget and funding, accountability, poor quality and ill-motivated teachers, shambolic learning environment, negative public perception of schools, poor quality infrastructure and teaching staff in the digital age, poor school attendance by students, and girl-to-boy ratio in school enrolment.

The Kwara conference was excellent on great ideas from participants on what to do, just as several academic conferences and summits elsewhere in Africa have been held to address such challenges.

Unfortunately, the will to put measures into practice is in dire want, though Kwara State attempted to show its exception with 25% budgetary allocation to education among other lofty feats.

No doubt COVID-19 has further bared the already shaky foundations of education in African countries, with efforts to contain the pandemic registering untoward effects on education.

The influential US think-tank, the Brookings Institution, has observed that whilst African leaders had their hands full with rising COVID-19 infections, fragile health systems, increasing food insecurity, and, in some areas, growing social unrest,” education was crucial to Africa’s COVID-19 response.

According to UNICEF, COVID-19 forced nationwide school closures in 23 countries worldwide; 40 implemented local closures, impacting about 47% of the world’s student population and more than 91% of students worldwide, with approximately 1.6 billion children and youngsters unable to attend physical schools.

The severest effects are in developing and less developed nations (Africa leading the troll) with disadvantaged children and their families, as the pandemic interrupted learning, compromised nutrition, childcare problems, and consequent economic cost to families who could not work.

The severest effects are in developing and less developed nations (Africa leading the troll) with disadvantaged children and their families, as the pandemic interrupted learning, compromised nutrition, childcare problems, and consequent economic cost to families who could not work.

School closures in response to the pandemic have shed light on various social and economic issues, including student debt, digital learning, food insecurity, and homelessness, as well as access to childcare, health care, housing, internet, and disability services.

COVID-19 also hit as Africa was reveling in rare economic growth and as its 54 countries had committed to creating the world’s largest common free trade area – the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) and Agenda 2063.

The latter aimed to provide “a blueprint and master plan for transforming Africa into the global powerhouse of the future”, where poverty, conflict and disease will be squarely addressed through sustained economic growth. Education was at the core of AfCFTA and Agenda 2063, with plans for a “skills revolution underpinned by science, technology and innovation.”

Speaking at the February 10, 2020 launch of the ‘First Continental Report on Implementation of Agenda 2063’, Vera Songwe, UN Under-Secretary General and Executive Secretary General of the UN Economic Commission for Africa, praised the optimism and vision of African leaders and their recognition of the importance of both communication technology and education to Africa’s future economic development. She however observed that the arrival of COVID-19 at a moment of such palpable optimism was regrettable, and that the pandemic presented a huge challenge to the education sector in particular.

We at Prime Business Africa believe that mere recognition of the importance of education and the need to use technology to drive it in the future are far from enough. We also align with Songwe’s position in saying that the pandemic represents not only a “wake-up call”, but also an opportunity for Africans to put technology at the heart of plans for using education to transform the continent.

We at Prime Business Africa believe that mere recognition of the importance of education and the need to use technology to drive it in the future are far from enough. We also align with Songwe’s position in saying that the pandemic represents not only a “wake-up call”, but also an opportunity for Africans to put technology at the heart of plans for using education to transform the continent.

If it is a surprise for Africa to support such views, as Songwe puts it, then Songwe could as well be mildly and subtly rebuking Africa for not doing a lot more than mere recognition of the importance of education.

She noted that, sometimes, the measures taken in the education sector were inadequate, patchy or confusing. Nigeria and the rest of Africa, for instance, have dozens of instances where education policy summersault, as was the case with Nigeria’s Almajiri school project in the North, has negated progress in more ways than one.

From Songwe’s comments, We at Prime Business Africa insist that now is the time for the continent to leverage some comparative advantages such as Africa’s changing demographic patterns, which are turning it into the world’s youngest continent.

Therefore, the changing demand in global labour markets because of technological developments alone amounts to a serious incentive to reform Africa through education.

For now, Africa’s young labour force has not translated to significant economic gains.

A 2018 report by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) has also made the link between education and poverty in Africa. The reports say that a far majority of the youth between ages 15 and 24 are uneducated, work in the informal sector, mainly subsistent agriculture in the rural areas.

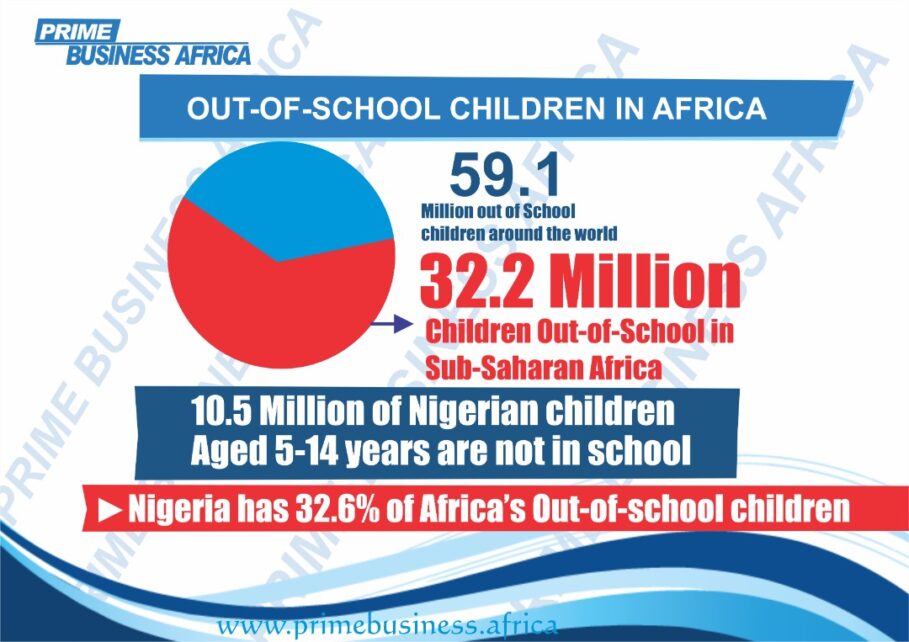

A report from Nigeria’s education ministry in June of 2021 noted that the country has the highest number of the out-of-school children (10,193,918) in sub-Sahara Africa, with high illiteracy level, infrastructural decay and deficits. A 2016 summary by OXFAM also revealed a 7.4 civilian firearms possession per 100 in 15 countries of sub-Saharan Africa, with the highest possession rate in South Sudan at 28.23 per 100 population.

Shortly before attending the UK summit, President Buhari, through his media aide, Mallam Garba Shehu, said Nigeria’s participation aligns with the president’s promises and assurance to emphasize education more, to increase funding to the sector.

Prime Business Africa believes that Nigeria’s President, like other African leaders who attended the conference, must certainly have listened to a festival of ideas on how to push the frontiers of education nearer to perfection. Of particular interest would be on their agreement to allocate at least 20% of national budgets to education, in deference to strong political commitments made by co-host of the conference, Kenya’s Uhuru Kenyatta.

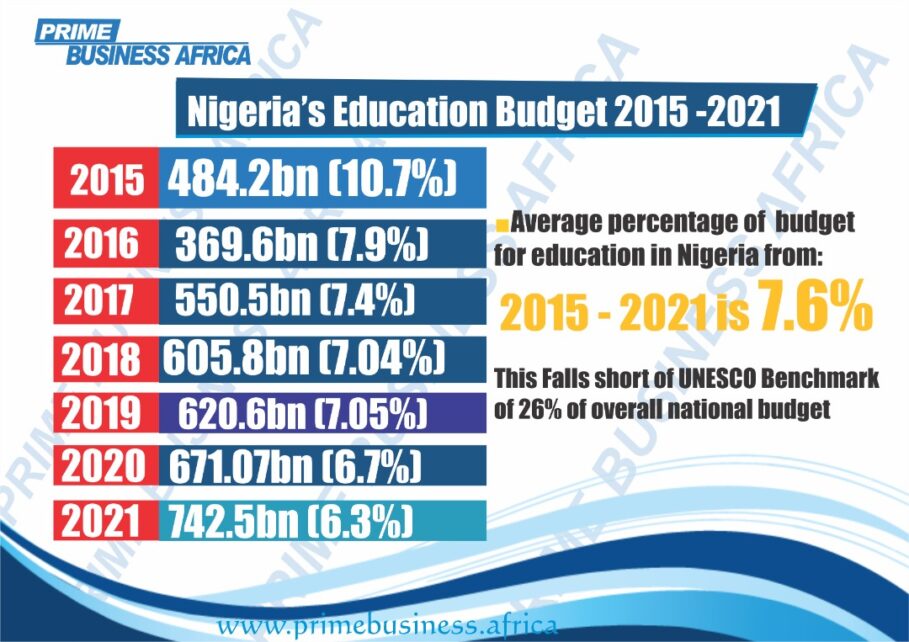

Notably, Nigeria had allocated 5.6%, the lowest since 2011, of its N13.6 trillion 2021 budget to education. UNESCO’s benchmark is 15-26%.

Average education budget in more than 30 countries of Africa (including Nigeria, South Africa and Ghana) over the past decade has hardly exceeded 7%. Such meagre allocation has been the root cause of frequent strikes in the education sector, as usually is the case with Nigeria .

The Academic Staff Union of Universities in Nigeria alone has gone on strike for a total of four years since Nigeria’s return to democracy in 1999, making strikes the most regular event in the academic calendar of tertiary institutions since 1999. One of the longest of the strikes ended just last December, after nine months.

Many of Nigeria’s graduates are ‘unemployable’ due to lack of skill, with thousands flocking to get-rich-quick online- fraudulent schemes or ready targets of insurgent groups as unemployment heightens.

Currently, 32.5% of Nigeria’s over 60 million labour force (about 23 million) are unemployed. This figure, having quadrupled in the last five years, is projected to rise to 33% in 2022.

Only Namibia, at 33.4% unemployment rate has a figure higher than Nigeria in the world. The ILO 2020 reports showed that the employment-to-population ratio for male and female workers in Africa stood at an average of 40%, while the extreme poverty rate stood at an average of 36.9 for male and female workers.

This situation has a clear link with rising food prices, insurgency, communal clashes, violence, kidnappings and banditry, which have held the continent hostage in the past decade.

The 2021 report of the Institute of Economics and Peace (IEP) on the economic value of peace, indicated that altogether insecurity and violence cost the country up to 8% of its GDP (about $132.59 billion or N50.38 trillion).

A 2021 United Nations report showed that insurgent groups such as Boko Haram and banditry have killed at least 350, 000 people, with more than two million displaced since 2009.

Insecurity has also led to 59.6% decline (from $23.99 billion to $9.68 billion) in capital inflow in Nigeria between 2019 and 2020, according to data from the National Bureau of Statistics. A report by OXFAM shows that $18bn per year is lost to Africa as a result of conflict.

To this end, we see the UK conference an example of a system in progress, and Africa needs to take serious lessons from some of the issues that trended at the summit such as re-orienting education towards change, transformation and social justice.

Students need to become in tune with globalisation and its many forms of growth and expansion within the context of the complex social, cultural, political, ideological and personal circumstances of this century. They need to learn how current trends cut across the world of education, and its subsequent impact on societies, institutions and individuals.

It is praiseworthy that the London conference raised $4 billion out of its projected $5 billion over five years. We, at Prime Business Africa, believe that the strategy of raise-your-hand donation, as was used during the UK Education conference, can be replicated in African countries with many good spirited multinational firms.

We also commend the recently launched EKOEXCEL and EdoBEST basic education programmes in Lagos and Edo States in Nigeria, respectively, which have leveraged partnerships to train and place thousands of government school teachers on the path of digital teaching and learning systems.

In response to COVID-19 disruptions in the education sector, UNESCO has recommended the use of distance learning programmes and open educational applications and platforms that schools and teachers can use to reach learners remotely and limit the disruption of education. Online learning may not be the panacea, given the benefits of conventional schooling.

For example, school performance hinges critically on maintaining close relationships with teachers, according to some experts. This is particularly true for students from disadvantaged backgrounds, who may not have the parental support needed to learn on their own. Yet working parents are more likely to miss work when schools close in order to take care of their children, incurring wage loss in many instances and negatively impacting productivity.

Unfortunately, UNESCO also remarks that in regions where online learning is not feasible, due to a lack of access to distance learning tools such as smartphones and internet connectivity, some parents have resorted to child labour or early marriage as a means to cope with the financial stress placed on them by the pandemic.

Online learning has therefore become critical support for education, as institutions seek to curtail the likelihood for community transmission.

Teachers from various places say that students are more likely to complete assignments on schedule when they access the internet at home. Books and other learning material can be accessed in different formats, transcending the barriers of time and space. Mobile devices, radio and television, video conferencing through Zoom, Google Classroom and/or Google Meet are in wide use.

This means that many low-cost measures are being implemented in places, and used to leapfrog the limitations imposed by COVID-19. Indeed, hardware, software, skill, cost, political will, needs prioritisation, public perception, access and user willingness to adopt technology are barriers and areas of need.

Participants at a recent e-learning summit in Rwanda in 2020 noted that e-learning was on course in Africa even before the coronavirus interlude. There are huge challenges, but progress can be made. The summit suggested learning from countries and other systems where it has worked.

Beyond the optimisms, recognitions, support, and well-worded policy statements on education seen so far in conferences, we insist that now is time for action!

Do you have any comments on this and other matters? Please send an email to editor@primebusiness.africa

![Gender Activism An Economic Necessity In Africa [PBA Editorial]](https://www.primebusiness.africa/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/vaw-720x480.png)

Follow Us