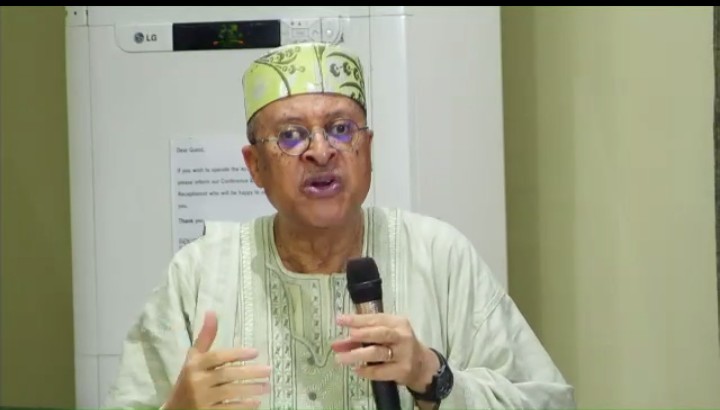

PAT Utomi – Leadership and Governance in Africa: Lessons from a Lifetime of Service

By Marcel Mbamalu, PhD

INTRODUCTION

The crisis of leadership in Africa has remained one of the most persistent obstacles to the continent’s political stability, economic development, and social cohesion. From the moment of political independence from the 1950s, African states have struggled to translate sovereignty into prosperity and freedom into accountable governance. These failures often stem from the nature of African societies as well as from administrative incapacity. Thus, in addition to leadership ineptitude, there are virulent historical and structural forces that have shaped African leadership outcomes.

Africa’s leadership dilemma is in fact the cumulative result of colonial distortions, global political economy, externally induced instability, and the systematic weakening of reformist leadership. Unfortunately, successive political elite in Africa insidiously profit from what looks like a cultural poor leadership context.

Join our WhatsApp ChannelWithin this troubled historical backdrop, the life and work of Professor Pat Utomi offer an alternative narrative. As a scholar, public intellectual, political actor, and civic advocate, Utomi represents a generation of African thinkers who refused to retreat into academic isolation or opportunistic politics. Instead, he has consistently engaged the public sphere, insisting that leadership must be grounded in ideas, ethics, and service. This essay situates Pat Utomi’s lifetime of service within Africa’s broader leadership crisis, drawing lessons for governance, democracy, and development.

Colonialism and the Structural Origins of Governance Failure

Colonialism fundamentally reordered African societies in ways that undermined indigenous systems of accountability and political legitimacy. Colonial administrations were extractive by design, focused on resource exploitation rather than nation-building. Arbitrary colonial borders in Africa grouped together disparate ethnic, religious, and political communities with little shared historical experience, as seen in Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Sudan, while also partitioning historically connected societies such as the Yoruba across Nigeria and the Benin Republic, and the Somalis and Tuareg across multiple states, thereby creating enduring legitimacy and leadership challenges for postcolonial governance. Governance structures emphasized coercion over consent, central authority over participatory rule, and economic extraction over social investment.

At independence, African leaders inherited states that were ill-prepared for democratic governance. Institutions such as the civil service, judiciary, and security apparatus were designed to serve colonial interests rather than popular sovereignty. The absence of strong civic traditions and inclusive political cultures created fertile ground for elite domination. Independence therefore marked not a clean break from colonial governance, but a complex transition in which colonial logics persisted under African leadership.

It is also common knowledge that some African leaders had articulated visions of rapid industrialization, social welfare, and continental solidarity. However, these aspirations soon collided with the realities of neocolonial dependency. Former colonial powers retained economic leverage through trade arrangements, multinational corporations, and financial institutions. Development assistance and loans were frequently tied to policy prescriptions that prioritized external interests over local needs.

As African economies became increasingly dependent on primary commodity exports, political leaders faced pressures to maintain stability for external partners rather than accountability to citizens. This dependency weakened democratic institutions and encouraged centralized, authoritarian governance. The promise of independence was thus betrayed not only by external manipulation but also by domestic elites who found personal advantage in inherited colonial structures.

For instance, in the immediate post-independence period, leaders such as Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana proclaimed bold agendas of state-led industrialization, social welfare, and Pan-African unity, projecting confidence that political freedom would translate into economic autonomy. Yet these ambitions were quickly undercut as former colonial powers and international financial institutions maintained decisive influence through commodity-dependent trade structures, multinational corporate control, and conditional loans.

Africa’s leadership crisis is further illuminated by the fate of reformist leaders who sought structural transformation. Patrice Lumumba of the Congo stands as the most emblematic case. His insistence on economic sovereignty and genuine independence made him intolerable to powerful external interests, leading to his removal and assassination. Lumumba’s fate sent a chilling message across the continent: visionary leadership carried existential risks.

READ ALSO: How HNIs Locked Down Prime Business Africa Colloquium In Otobo’s Honour

Nigeria’s recent political history illustrates this trend too. The emergence of Muhammadu Buhari’s presidency in 2015 was widely framed internationally as a reformist alternative to entrenched corruption. However, his immediate predecessor, former President Goodluck Jonathan’s public reflections and subsequent national debates have raised questions about the extent to which external validation shaped domestic political expectations. For many Nigerians, the Buhari administration failed to deliver the transformative change that was promised. This episode underscores how global legitimacy can be manufactured in ways that hide local realities and weaken democratic accountability.

Structural Failures and Contemporary Manifestations

Africa’s governance crisis manifests most visibly in persistent institutional weakness, democratic regression, and declining state capacity to deliver public goods. To be candid, with over 60 years since independence, there is ample blame on corrupt leaders or incompetent administrations.

One major manifestation is the erosion of democratic norms. Across the continent, elections increasingly coexist with shrinking civic spaces, judicial manipulation, and executive overreach. Even in formally democratic states, governance outcomes remain poor due to prebendal politics and the personalization of power (Cheeseman, 2018). Utomi (2013) characterizes this as a leadership crisis rooted in the abandonment of values, where public office becomes an avenue for private accumulation rather than public service.

Economic governance failures further exacerbate this crisis. Rising inflation, unemployment, and debt servicing burdens have weakened the social contract between African states and their citizens. In Nigeria, inflation surpassed 30% in 2024, driven by currency depreciation, fuel subsidy removal, and import dependence. Similar inflationary pressures have been recorded in Ghana, Egypt, and Sudan, eroding real incomes and intensifying popular discontent (World Bank, 2024). These conditions create fertile ground for political instability and legitimize authoritarian or military “corrective” interventions.

Security governance has also deteriorated. Insurgency, banditry, and transnational terrorism persist across the Sahel, Lake Chad Basin, and Horn of Africa. Civilian governments’ perceived inability to address insecurity has been a recurring justification for military takeovers in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger. However, evidence suggests that military regimes often struggle to improve security outcomes, instead deepening international isolation and economic hardship (International Crisis Group, 2024).

Crucially, these governance failures are not isolated. They intersect with global economic shocks, climate stress, and external security agendas, reinforcing what Utomi (2020) describes as a cycle of governance vulnerability, where weak institutions invite external intervention, which in turn further weakens domestic accountability.

Post-Colonial Africa as a Strategic Chessboard

Africa’s disadvantaged governance position is inseparable from its location within contemporary global power rivalries. As we have already seen, the post–Cold War unipolar moment has given way to a multipolar contest involving the United States, the European Union, China, and Russia. Each of these power centres is pursuing distinct but overlapping interests on the continent. In this contest, Africa frequently appears less as a rule-maker and more as a terrain for strategic competition.

Western engagement in Africa after independence continues to emphasize democracy promotion, counterterrorism, and market liberalization. However, critics argue that Western policies often prioritize security cooperation and migration control over genuine democratic accountability, particularly in the Sahel and North Africa (Taylor, 2019). This selective commitment undermines normative consistency and weakens domestic reform incentives.

China’s growing presence, by contrast, is anchored in infrastructure financing, trade, and resource extraction. While Chinese investments have contributed to visible infrastructural development, they have also raised concerns about debt sustainability, transparency, and environmental governance. Several African countries now face heightened debt exposure to Chinese lenders, limiting fiscal autonomy and policy space (AfDB, 2024).

Russia’s engagement has taken a more overtly security-centered form. Through military cooperation agreements and private military contractors, Russia has positioned itself as an alternative partner for regimes facing Western sanctions or legitimacy deficits. In Mali, the Central African Republic, and Burkina Faso, Russian involvement has reshaped governance trajectories, often strengthening coercive state capacity at the expense of democratic accountability (Dunn & Shaw, 2023).

These external power plays interact with domestic elite interests, producing what Ndlovu-Gatsheni (2020) terms “entangled sovereignties.” African leaders navigate global alliances strategically, but often in ways that prioritize regime survival over citizen welfare. As a result, governance outcomes are shaped as much by external bargaining as by internal democratic processes.

Utomi’s intervention is critical here. He argues that Africa’s governance weakness persists because leadership has failed to articulate a coherent moral and developmental vision capable of resisting exploitative global arrangements (Utomi, 2011). Without values-driven leadership, external partnerships, whatever their origin, are often on the edge of reproducing dependency and governance failure.

African Intellectuals and the Struggle for Renaissance

Despite these constraints, Africa has never lacked thinkers committed to renewal. Across generations, African intellectuals have challenged dominant narratives, critiqued power structures, and articulated alternative futures. These figures have operated at the intersection of scholarship and activism, refusing to separate ideas from action. For decades, intellectuals in Africa have remained a very formidable social conscience, almost the only veritable opposition to government.

Professor Pat Utomi belongs firmly within this tradition. His work reflects a conviction that Africa’s crisis is fundamentally a leadership and values deficit rather than a shortage of resources or talent. Through research, advocacy, public lectures, and civic mobilization, he has consistently argued for ethical leadership, institutional reform, and citizen participation as foundations for sustainable development.

Central to Utomi’s influence is his extensive body of scholarly and public writings. His books interrogate the structural roots of underdevelopment and the failures of leadership. Across these works, Utomi advances a consistent argument: that democratic governance, ethical leadership, and productive economic institutions are inseparable. Some of the books are The Challenge of Nigeria, Why Nations Are Poor, Can Africa Rise, and Economic Reforms and the Nigerian Economy.

Beyond written scholarship, Utomi’s public lectures and keynote addresses at universities, policy forums, and civic gatherings have reinforced these ideas. His speeches on democracy, economy, and governance emphasize the moral dimensions of leadership and the responsibility of citizens to demand accountability.

Case Points from Scholarship

As already noted, Africa’s governance crisis cannot be understood merely as a product of domestic leadership failures or institutional weaknesses. Rather, it is embedded within a complex historical, geopolitical, and economic matrix in which internal governance deficits overlap with external power interests and structural dependencies. From the post-colonial era to the present, African states have remained disproportionately vulnerable to external manipulation, elite capture, and global economic shocks, all of which continue to undermine democratic consolidation and developmental governance (Utomi, 2013; Ake, 2001).

In recent years, this vulnerability has become more pronounced. Between 2020 and 2024, Africa experienced an unprecedented resurgence of military coups, particularly in West and Central Africa, including Mali (2020, 2021), Guinea (2021), Burkina Faso (2022), Niger (2023), and Gabon (2023). While these coups are often framed domestically as reactions against corruption, insecurity, and elite failure, scholarly and policy analyses increasingly point to foreign geopolitical undercurrents shaping their trajectories. The strategic repositioning of Russia (notably through Wagner-linked security arrangements), China’s expanding economic leverage, and Western efforts to retain political and military influence have turned parts of Africa into contested governance spaces within a renewed global power rivalry (Dunn & Shaw, 2023; International Crisis Group, 2024).

Africa’s economic governance environment has simultaneously deteriorated. Inflationary pressures, worsened by global supply chain disruptions, the Russia–Ukraine war, currency depreciation, and debt distress, have battered state legitimacy and intensified citizen dissatisfaction. As of 2023–2024, several African economies recorded double-digit inflation rates, with countries such as Nigeria, Ghana, Egypt, Sudan, and Zimbabwe experiencing sustained price instability that weakened purchasing power and intensified governance pressures (World Bank, 2024; African Development Bank [AfDB], 2024). These economic stresses deepen what Utomi (2011) describes as the crisis of political economy, where states lose both moral authority and material capacity to govern effectively.

Within the global system, Africa continues to function less as an autonomous political actor and more as a strategic arena. The United States and the European Union emphasize democracy promotion, counterterrorism, and market access, while China and Russia foreground infrastructure financing, security partnerships, and regime-to-regime engagement. This power competition often sidelines African citizens and institutions, reinforcing elite-centered governance and weakening accountability structures (Taylor, 2019; Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2020). As Utomi (2020) warns, Africa risks remaining a “policy-taking continent” rather than a “policy-shaping one” unless governance is re-anchored in ethical leadership and citizen-centered development.

Conceptual and Theoretical Framing

Governance, in contemporary political analysis, extends beyond the formal exercise of state authority to include the processes through which power is negotiated, resources are allocated, and collective goals are pursued within and across societies (Hyden, 2018). Utomi’s political economy perspective situates Africa’s governance crisis within a wider ethical and leadership deficit. He argues that governance failure is sustained by the collapse of values, the capture of the state by rent-seeking elites, and the erosion of public-spirited leadership (Utomi, 2013; Utomi, 2020). While earlier African governance literature emphasized post-colonial state fragility (Ake, 2001; Bayart, 2009), newer scholarship integrates global structural forces, including neoliberal conditionalities, security externalization, and geopolitical competition (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2020; Mkandawire, 2019).

From a political economy and dependency theory lens, Africa’s governance challenges reflect its subordinate position within global capitalism. Contemporary debt regimes, foreign direct investment patterns, and security partnerships often reproduce dependency rather than autonomy. China’s infrastructure-for-resources engagements, Russia’s security-focused alliances, and Western aid-conditional governance frameworks each shape domestic governance outcomes in different, but equally constraining ways (Taylor, 2019; Dunn & Shaw, 2023).

The resurgence of coups further illustrates this intersection of domestic grievance and external structure. While military takeovers are justified by coup leaders as corrective interventions against civilian misrule, their sustainability often depends on external recognition, economic lifelines, or security backing. This dynamic underscores what Ndlovu-Gatsheni (2020) describes as the “externalization of African sovereignty”, where governance legitimacy is partly negotiated outside the continent.

Importantly, newer governance literature challenges earlier optimism about democratic transitions by highlighting the limits of electoralism in contexts of economic precarity and geopolitical intrusion (Levitsky & Way, 2020; Cheeseman, 2018). When inflation, unemployment, and insecurity persist, democratic institutions struggle to deliver legitimacy, creating openings for authoritarian alternatives—both civilian and military.

Utomi’s contribution remains indispensable here because it bridges ethics, leadership, and political economy. Unlike purely structural accounts, he foregrounds the agency of African leaders and citizens, arguing that moral leadership and institutional reform can still reclaim governance space, even within an unequal global system (Utomi, 2011; 2020). Placing Utomi alongside newer global analyses therefore allows for a balanced framework—one that neither absolves African elites nor ignores the weight of global power asymmetries.

Reclaiming Governance Space: Ethical Leadership, Institutional Reform, and Strategic Autonomy

Despite these constraints, Africa’s governance predicament is not irreversible. A growing body of scholarship emphasizes the possibility of agency within structure, arguing that ethical leadership, institutional reform, and strategic engagement with the global system can reposition African states (Mkandawire, 2019).

Ethical leadership remains central. Utomi consistently stresses that governance reform must begin with values such as integrity, service, accountability, and competence. Without these, institutional reforms will only become procedural exercises devoid of substance (Utomi, 2020). Ethical leadership also enhances legitimacy, enabling governments to mobilize citizens and negotiate external partnerships from a position of credibility.

Institutional strengthening is equally important. Independent judiciaries, professional civil services, and transparent public finance systems can buffer states against elite capture and external manipulation. Recent governance gains in countries such as Botswana, Mauritius, and Rwanda (though with known limitations) demonstrate that institutional coherence matters for developmental outcomes (Hyden, 2018).

At the global level, Africa must pursue strategic autonomy rather than alignment dependency. This does not imply isolationism, but a deliberate recalibration of external engagements to prioritize long-term development and governance results. Regional integration frameworks, such as the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), offer pathways for reducing external vulnerability and enhancing collective bargaining power.

Ultimately, reclaiming governance space requires a synthesis of internal reform and external repositioning. As Utomi argues, Africa’s challenge is not the absence of ideas, but the absence of leadership committed to translating ideas into ethical governance practice within a hostile global environment. Bridging this gap is essential if Africa is to move from being a subject of global power politics to an active participant in shaping them.

When situated within Africa’s troubled leadership history, Pat Utomi’s lifetime of service offers enduring lessons. Principled leadership is possible even within hostile political environments. Ideas matter, and sustainable change requires intellectual clarity and moral courage. Institutions, far more than personalities, are the foundations of development.

As the ilk of Pat Utomi retire, the intellectual community is hereby challenged to taken on the baton, the academic torch and push the boundaries of scholarship despite the endemic challenges. A lot of courage is needed because the world of the intelligentsia in countries like Nigeria is increasingly coming under major stress. A lot of this stress appears to be state-induced and we must take note.

For instance, some of the effects of battles between government and university unions as well as the leadership crisis in tertiary institutions over the past decade are quietly showing up. The Nigerian government appear to steadily thwart the laws on institutional autonomy, frustrating governance structures in the civil service space. Between 2017 and 2022, industrial action from civil service based unions consumed over two years, sacrificing academic leadership and hugely distracting the federal government, which prioritized power centralization over effective governance. The recent change in the governing council of many federal universities is also having its own impacts. In Nigeria, politicians appear to have invaded the academic space, threatening or crippling a major of source of knowledge for national development. As we speak, this problem has added to the strain of the free falling academic standards.

Indeed, Africa’s governance challenges are deeply historical and structurally reinforced, but they are not immutable. The continent’s future depends on reclaiming leadership as a moral vocation grounded in service, accountability, and intellectual thoroughness. In celebrating Pat Utomi’s lifetime of service, this essay affirms the enduring relevance of engaged scholarship and ethical leadership in Africa’s long struggle for renaissance.

References

African Development Bank. (2024). African economic outlook 2024. AfDB.

Ake, C. (2001). Democracy and development in Africa. Brookings Institution.

Bayart, J.-F. (2009). The state in Africa: The politics of the belly (2nd ed.). Polity Press.

Cheeseman, N. (2018). Democracy in Africa: Successes, failures, and the struggle for political reform. Cambridge University Press.

Dunn, K. C., & Shaw, T. M. (2023). Africa in global politics: Engaging a changing world order (3rd ed.). Lynne Rienner.

Hyden, G. (2018). African politics in comparative perspective. Cambridge University Press.

International Crisis Group. (2024). Africa’s coup belt: Causes, consequences, and responses. ICG.

Levitsky, S., & Way, L. (2020). Revolution and dictatorship: The violent origins of durable authoritarianism. Princeton University Press.

Mkandawire, T. (2019). Social policy in a development context. UNRISD.

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. (2020). Decolonization, development and knowledge in Africa. Routledge.

Taylor, I. (2019). Africa rising? BRICS, diversifying dependency. James Currey.

Utomi, P. (2011). Why nations fail: The Nigerian case. Spectrum Books.

Utomi, P. (2013). Mind the gap: Leadership, ethics and governance in Africa. Ibadan University Press.

Utomi, P. (2020). Values, leadership and national transformation. Centre for Values in Leadership.

World Bank. (2024). Africa’s pulse: Navigating inflation and debt distress. World Bank.