From the ancient walls of Benin City comes a timeless proclamation “Isẹlogbe!” a greeting that marks not only the dawn of a new year but also one of the most sacred celebrations in Edo tradition: the Igue Festival.

Rooted deeply in the spiritual and cultural heritage of the Benin Kingdom, the Igue Festival stands as a living testament to the Edo people’s enduring reverence for their ancestors, their monarch, and Osanobua, the Supreme God.

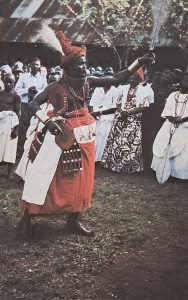

Join our WhatsApp ChannelEvery December, the Benin Kingdom transforms into a living museum of culture. The royal palace glows under the sun’s bronze shimmer, coral beads glint on the necks of chiefs and maidens, and the streets fill with the rhythm of ancestral drums.

The city’s air carries an unmistakable scent, a mix of burning incense, fresh palm leaves, and the sacred ewere leaf that symbolizes victory and renewal. It is Igue season, a time when the living commune with their ancestors and when gratitude takes on the form of dance, prayer, and ritual.

A Festival Older Than Time

While modern calendars may mark the Igue Festival as an annual cultural event, to the Edo people, it is the spiritual heartbeat of their civilization, a festival as old as the kingdom itself.

Some historians trace its beginnings to the Ogiso era, predating the reign of Oba Eweka I, when the early inhabitants of Benin practiced personal thanksgiving rituals known as Igue Uhunmwun, the blessing of one’s head.

But the festival, as known today, gained structure and royal prestige under Oba Ewuare the Great (1440–1473). Before his coronation, the young Prince Ogun endured years of exile and betrayal in his quest to reclaim the throne. When destiny finally smiled on him and he became king, he vowed to dedicate a festival of thanksgiving to Osanobua and the ancestors. That vow birthed the Igue Festival, a covenant of gratitude, renewal, and divine favour.

“Oba Ewuare instituted Igue after surviving great trials,” the late Chief David Edebiri, Esogban of Benin Kingdom, once explained. “It is not pagan, it is our thanksgiving service. We thank God Almighty through our head, which has carried us throughout the year.”

The name Ewuare, derived from Owoura meaning ‘all is well’, became a spiritual declaration, a reminder that from struggle can emerge peace, from exile, triumph.

Ritual of the Head – The Seat of Destiny

Central to the Igue Festival is the Igue Uhunmwun, the thanksgiving and purification of the head. In Edo cosmology, the head (uhunmwun) is not merely a physical part of the body; it is the carrier of destiny, the point through which man communicates with Osanobua. The Oba, regarded as both king and divine intermediary, blesses his head and those of his subjects, ensuring a harmonious balance between the spiritual and physical realms.

The Oba’s rituals, performed within the sacred palace precincts, are shrouded in reverence and secrecy. During this period, the monarch enters seclusion, no foreign visitor is allowed to meet him, as he communes spiritually on behalf of the kingdom. Each prayer, each symbolic act, is directed toward ensuring fertility of the land, prosperity of the people, and continuity of the royal dynasty.

“Just as Christians go to church at year’s end to thank God,” Edebiri said, “the Edo people gather to thank Osanobua for keeping them alive and to ask for blessings in the new year.”

Symbolism of the Ewere Leaf

The Ewere (Ebowere) leaf occupies a sacred place in the festival’s rituals. According to legend, Oba Ewuare discovered the leaf during his exile, a plant that miraculously soothed his pains and gave him renewed strength. It thus became the emblem of peace, healing, and divine favour.

Each year, young men and women enter the forests singing ancient songs to pluck the Ewere leaves. Their return to the city is a scene of jubilation, streets echo with laughter as people exchange greetings of “Ewere!” and respond, “Isẹlogbe!” It is both benediction and celebration , the Edo equivalent of wishing one another a blessed new year.

Homes, markets, and even vehicles are adorned with the green leaves, believed to ward off evil and invite blessings. In essence, the leaf connects the kingdom’s ancient spiritual roots with its present-day hopes for peace and prosperity.

READ ALSO: Ovia-Osese Festival 2025: Where Purity Meets Pride in the Heart of Kogi

Onitsha Ofala Festival: A Celebration of Tradition, Renewal, Unity

Ugie Ceremonies

The Igue Festival is part of a broader cycle known as Ugie, a series of royal ceremonies that stretch across December. Each phase tells its own story of triumph, remembrance, and renewal:

- Ague: a fasting period of spiritual cleansing, during which funerals are suspended and the kingdom enters solemn reflection.

- Ugie Iron: a re-enactment of the Oba’s victory over evil, showcasing the symbolic clash of good and malevolence.

- Ugie Erha’Oba: the Oba honours his royal ancestors in elaborate sword dances, the Ẹbẹn blade flashing in rhythmic movement.

- Igue Oba: the principal rite of head purification, performed in seclusion at Ugha Ọzolua.

- Ugie Ewere: the joyous conclusion of the festival, when the Oba bestows blessings upon his people with the Ewere leaf.

Through these stages, the entire kingdom becomes a sacred theatre, its rhythm dictated by chants, drumbeats, and rituals echoing through time.

Ten Blessings of Igue

The festival culminates in prayers for the Ten Blessings of Igue, encapsulating the Edo philosophy of wholeness and prosperity:

1. Afiangbe – Abundance and divine favour.

2. Akugbe – Unity and togetherness.

3. Alaghodaro – Progress and advancement.

4. Ẹfe vbe Igho – Wealth and prosperity.

5. Egberhanmwen – Good health and strength.

6. Ofumwengbe – Peace and reconciliation.

7. Oghogho – Joy and happiness.

8. Omo – Fertility and fruitfulness.

9. Oyenmwen – Contentment and satisfaction.

10. Utomwen – Longevity and fulfilment.

These blessings, chanted in songs and prayers, reinforce Igue as both spiritual contract and national philosophy, an annual renewal of hope.

Ancestral Drums and the Pulse of Identity

To walk through Benin during Igue is to feel history vibrating in one’s bones. The drums, the chants, the coral-red of regalia, the scent of incense, all evoke a civilization that has endured colonization, wars, and modernization yet still guards its soul fiercely.

Cultural custodian Chief Omoregie Edebiri, speaking at a recent Ugie ceremony, described it as “a moment when time collapses when the living, the dead, and the unborn commune in the presence of Osanobua.”

The rhythm of the royal drums (ẹkpẹ) is not mere music. Each beat communicates a coded message to the ancestors and the deities, a language only the initiated fully understand. It is said that even the winds pause over the Benin moats when the Oba’s procession passes such is the reverence of the land.

Global Celebration of Heritage

Today, the Igue Festival transcends geography. Edo sons and daughters in the diaspora – from London to Houston, Toronto to Johannesburg – hold their own Igue celebrations, complete with prayers, dances, and blessings of the Ewere leaf. The event has become a cultural anchor for second-generation Edo descendants seeking to reconnect with their roots.

Modern influences have also found their place. The palace now permits cultural performances, academic exhibitions, and tourism-friendly activities around the festival’s periphery, though the core rites remain untouchable. Local artisans display bronze works, musicians perform traditional rhythms blended with Afrobeat, and visitors from across Nigeria and abroad flock to witness the royal pageantry.

“It’s not just a festival,” said Dr. Ehizogie Iduware, a cultural historian at the University of Benin. “It’s the living proof that the Edo civilization still breathes – dignified, spiritual, and unbroken.”

Faith, Identity, and Continuity

In a nation often divided by politics and religion, the Igue Festival offers a rare glimpse into unity rooted in gratitude. While Christianity and Islam dominate Nigeria’s religious landscape, many Edo Christians still attend Igue, seeing it as thanksgiving rather than idol worship. Even Catholic priests and Muslim scholars have acknowledged its deep moral foundation, gratitude, peace, and family renewal.

“The Igue Festival teaches values that every faith shares – thanksgiving, peace, and love,” said a participant, Osayomore Uhunamure. “It reminds us that being modern does not mean losing who we are.”

Eternal Light of the Kingdom

As night descends on the palace, coral beads shimmer beneath torchlight. The Oba, draped in pristine white, lifts his Ẹbẹn sword skyward, offering blessings to the kingdom. Drums thunder. Bells ring. Chants of “Ewere! Ewere! Isẹlogbe!” ripple across the courtyards.

The Igue Festival closes not with fireworks, but with solemn beauty, a reminder that for the Edo people, gratitude is eternal, identity is sacred, and heritage is divine.

And as the echoes fade into the night, the ancient kingdom whispers once again the words that have outlived empires and centuries:

“Isẹlogbe!” May peace, prosperity, and renewal reign eternally in Benin Kingdom.

Amanze Chinonye is a Staff Correspondent at Prime Business Africa, a rising star in the literary world, weaving captivating stories that transport readers to the vibrant landscapes of Nigeria and the rest of Africa. With a unique voice that blends with the newspaper's tradition and style, Chinonye's writing is a masterful exploration of the human condition, delving into themes of identity, culture, and social justice. Through her words, Chinonye paints vivid portraits of everyday African life, from the bustling markets of Nigeria's Lagos to the quiet villages of South Africa's countryside . With a keen eye for detail and a deep understanding of the complexities of Nigerian society, Chinonye's writing is both a testament to the country's rich cultural heritage and a powerful call to action for a brighter future. As a writer, Chinonye is a true storyteller, using her dexterity to educate, inspire, and uplift readers around the world.