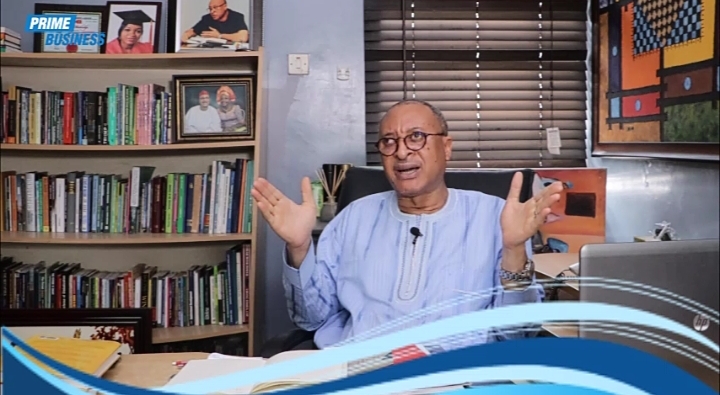

RENOWED Professor of Political Economy and founder of Centre for Values in Leadership, Professor Pat Utomi who marks his birthday today, February 6 2022, in this exclusive interview with Prime Business Africa’s VICTOR EZEJA and DAVID OBISESAN speaks on his life, growing up, educational background, involvement in social and political activism and how forces in Nigeria’s political system have affected his dreams of a better nation and ruined the lives many citizens.

Prof. as you mark your 66th birthday, can you tell us about your most challenging moment in life?

There are many reasons to reflect and when I reflect, I can identify dozens of extreme, extraordinary moments. To categorize them as to which was the most challenging is difficult to do, but I can tell a few of them. As I am marking my 66 years on this planet, I reflect on the very important story of my journey in the country that I have been privileged to be part of since it was formally granted independence. I wrote an article titled “I watch them still my life”. It is a reflection of one waking up with a promise, a country of promise and watching that promise wasted by some people, compatriots; some of them meaning well, some of them driven by obsessive self-love. The bottom line is that they wasted my life.

Join our WhatsApp ChannelWatch the video here:

I tell a story that people find incredible to believe. As a nine-year-old, unaccompanied, I got on the train in a place called Guzau in today’s Zamfara State. I travelled to Kaduna, and changed train, boarded the one going to Enugu; getting to Enugu, I got off the train, and got on a bus to Onitsha; and later returned to Guzau as a nine-year-old, unaccompanied. Today, a 24-year-old is going to do NYSC in Abuja from Lagos, his mother gets on the plane with him, gets him a place of residence, and then with her hearts literally in her hearts, returns to Lagos. How did we fall so low!? You can explain somehow, how we fell.

How did he still my life? The first major raw deal that we can think of is on my 18th birthday. I was in the University of Nigeria Nsukka. In the years before that, there had been student demonstrations following the killing of a student called Kunle Adepeju two or three years earlier by the Police. In the demonstration, police stray bullet, killed this young man. When I was at St. Ignatius of Loyola College in Ibadan, I had a lot of friends, brothers (some of them older) in University of Ibadan (UI), so I knew the UI terrain very well. Then the Adepeju killing incident sank in me.

Late in 1973, every university shutdown except the University of Nigeria because they were demonstrating against the Adepeju’s killing. As if something was wrong that we in Nsukka were going to school. I could understand why many students in the University of Nigeria had lost three years to the civil war, so they were so embittered about how others did not respond to their own plight, but couldn’t deal with an understanding of a shared humanity that was not more universal.

I frequently talk about how I came to understand citizenship; I talk about the whole Greek categorization of human beings. At the lowest level of humanity are the people who just think of themselves. When they make progress, they arrive at a circle level. These are the people who think of only those that are related to them, either by blood, language, or some primordial kind of thing. These people they call tribesmen, tribalists. The completeness of humanity is in citizenship, in shared values where the death of another man diminishes you no matter where you are from, because we all have shared humanity.

So approaching the problem of that moment from that perspective, I was not going to accept becoming a tribalist, rather than a citizen. I thought something was wrong, so I began to gather groups of persons and said we must do something about this. We started trying to find people who could think like us. We found a couple of them. We began to meet in my room and asked ourselves what we should do about the situation. Then we found another student who was known for his politics, who was trying to do a similar thing. He was the legendary Bassey Ekpo Bassey. So we merged with him and became the Student Democratic Society. We meet every day, sometimes we plan demonstration.

On the night of the 5th of February, we met for long up until midnight and went back to our rooms. By 5 am we were all out wearing black and black, and began to parade, went round the campus and some people woke up from their sleep and looked out to see us and said “umu ewu a!” “useless boys, go back and sleep!” we were meant to reach the university gate and make the world know that students of university of Nigeria are in solidarity with all the other students in Nigeria. but somewhere along the line a certain student who observed me who we generally referred to as a certified professional undergraduate who by our calculation had spent close to thirteen years in the university, who was called ‘chairman Pinick’ saw us demonstrating and quickly put on his cloth and joined us. As we were heading towards the gate, he diverted us to the vice-chancellor’s house. In front of the vice-chancellor’s house, the vice-chancellor granted us permission to have student rally. He, Pinick was giving a speech during the student rally around 8pm at Margaret Ekpo Hall, and he said “today the 6th of February, 1974, will be remembered as a day when those who were physically demobilized after the civil war were finally mentally demobilized” and everybody responded “heeeey”. So I stopped and said oh my God, it’s my birthday. I had forgotten my 18th birthday. That’s one of the first things they stole from me, my 18th birthday.

There are many reasons to reflect and when I do, I can identify dozens of extreme extraordinary moments. Going back to my childhood, it was shaped first and foremost, by the very Nigerian nature. I was born in Kaduna and baptized three months later in Jos which was where my family lived in 1956, my father was transferred to Maiduguri, and spent one and half years of my life in Maiduguri, then my father was transferred again to Kano. My father worked for British Petroleum in those days.

I started school in 1960 when my father was transferred to Guzau. The bulk of my primary education took place in a catholic school called Our Lady of Fatima in Guzau. By that time, I was a young chap, waking up 5 am every day to come and set up and serve mass in the mornings at Our Lady of Fatima. Then, John F. Kennedy was the president of the United States of America, the parish priests and reverend brothers there were Americans primarily, and so you can imagine how much the Kennedy mystic affected my early years. So I heard those phrases “ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country,” a zillion times. When we had competition amongst the altar boys I typically won, and the gift was typically a book about Kennedy or by Kennedy. So my reading culture was set very early by the reading of those books; the molding of the character was significantly informed by those moments in Guzau.

My first huge shock actually was during the Nigerian Civil War the trauma of it was incredible for a young person who was exposed to a lot in early life. I was at Christ the King College in Onitsha when the civil war started. I watched the Asaba Massacre literally and myself escaped being shot during the Mid-West imbroglio of the civil war. People forget that that part of the civil war was typically the worst genocide of the 20th century short of the Jewish Holocaust in Germany. So living through that was a huge trauma but it was made a literally interesting one because I didn’t live throughout the civil war on the Biafran side. Sometime in 1968, I was already back in Lagos where my father was and I was going to school in Ibadan at Loyola College. That experience opened the way to quite a number of other experiences.

In the university, I became very active in student life. The first major one was helping quite a number of students organize how to react to closing a number of Nigerian universities in late 1973 and early 74, following demonstrations on the Adepeju killings in Ibadan. From then I became quite active as a student leader. In 1975, I had a remarkable experience that would define my time at the University of Nigeria. I was shocked a few years ago visiting when somebody called my attention to a book on “50 years of SUG in UNN”, and they celebrated my contribution based on one thing which is that in 1975, I was convinced that students had a right to influence national policy. The biggest issue in Nigeria in 1975 was foreign policy; the liberation movement in Southern Africa. I then decided to challenge the foreign affairs ministry to come and explain to us the choices that they were making in Nigeria’s position on Southern Africa. We were called the frontline state even though we were not in the frontlines because of Nigeria’s involvement in that which was a great thing and we wanted to understand why Nigeria was making certain kinds of choices and not other kinds of choices. So I approached the foreign minister on this for him to come and debate with us. The way that I saw the world, I didn’t realize that I was being a precocious student to assume that the government owed us the responsibility to explain the decisions they were going to make. Of cause I didn’t get a reply to my letter, and so I decided to march to the foreign minister’s office. I came into Lagos from Nsukka, and early that morning I went to the foreign minister’s office. A coup had just taken place in Nigeria removing General Gowon as head of state with new government in place and the new foreign minister is the guy who just announced the coup. So you can imagine the kind of security around him. Young people who have not lived through the military era cannot understand where we are coming from. The motorcade sometimes included amoured cars and stuffs like that. So, I gained entrance. When I got to his office and announced the purpose of my visit, the secretary looked at me and was like ‘look at this boy, you want him to come and explain to you.’ He said ‘okay, when you go back to school, write to the dean of students affairs who will then take it to the vice chancellor so it can reach us through that. I said madam by then I would have graduated. She said, ‘yes, your successor would continue.’ So I found out that she was not about to be helpful at all. So I decided to get to the man through another way. I went down and asked the concierge when the foreign minister normally arrives in the office; the next thing I saw is that he on a motorcade pulled up. I stepped out and said ‘Colonel Garba, I disagree with your position on Angola.’ He was like ‘who said that’. I said ‘I am the one.’ He said ‘who are you’ I said ‘I am Pat Utomi from the University of Nigeria.’ Then he said ‘why do you disagree?’ I wanted that to be the point of engagement.

One of the advantages of our time, which I hope young people would learn from it, is that as at the age of 14, I read Time Magazine and News Week from cover to cover every week. There was no issue on this planet that I could not take you on.

So I began to tell him what I thought were the issues in Angola and he was quite precocious himself that we began to argue over it. We were doing that when we walked past his secretary into his office. The secretary that had bounced me out was like what’s he like, where has this boy come from. He immediately called her and asked her to bring in his special Adviser, Ambassador Brownson Dede. As Dede came in, he said I am going to Nsukka to debate these boys, what do you they mean. So I knew I had won. Now we agreed to a date the next year, February 1976. But what we did not know when we were agreeing was that three days before that date, another set of coup plotters would remove the head of state. So Nigeria was in total turmoil. When that happened, we were in the streets protesting against the coup before we even knew who was in the coup. Nobody could give us information on whether he was going to still come because the telephone lines across the country were cut, because that’s the first thing soldiers use to do before a coup. So, we couldn’t reach Lagos. I went to Enugu to the governor’s office, but none knew whether he is coming or not. One of the guys said if he is going to come, he would come through the airport, why don’t you go and stay at the airport and start waiting. At that point I really had no choice but to the airport. Barely 15 minutes after I got to the airport, a jet landed and out came Colonel Joseph Garba. In the heat of a national crisis, he had chosen to honour his word to me. I never forgot that. Even the vice chancellor, nobody took us seriously that he would come, now there was crisis, everybody dismissed the thought of his coming. So when Radio Nigeria Enugu announced that the foreign minister has arrived Enugu on his way to Nsukka, the entire campus erupted. It would become an interesting highlight of my Nsukka years.

Leaving the university, a precocious 21-year-old who believed the world would be fixed, I went straight into journalism. There was the leading news magazine in the country at the time called NewBreed magazine published by Chris Okoye. I showed up to do my national service at NewBreed. I wrote investigative stories that resulted in cabinet reshuffles at 21, and I thought we would build a great country. At that time, Mao had just died and Ye Ping was rising in China. China’s GDP was then half that of Nigeria per person. You will know that these fellows stole my life when I would be alive at a time when China’s output per person would be 30 times that of Nigerian, these guys stole my life.

At that time, China wasn’t even my concern. My great concern was what the military was doing in South Korea, how they were transforming the country, and our own military was taking us to another direction. Then, Nigeria was generally considered country of great prospects than South Korea, but we saw the military coup begin to transform things in South Korea. Industrialization took off.

In 1960, 10 percent of Nigeria’s GDP was coming from manufacturing, even though the colonial administration invested nothing in manufacturing and when self government came, it led to a massive commitment to industrialization. Between 1957 and 1960 manufacturing had moved from next to zero, to 10 percent of GDP In spite of the huge nature of agricultural commodity economy. But would live to see Nigeria achieve 10 percent of her GDP in manufacturing and begin a decline to about two percent of our GDP. These guys stole my life.

I attended a conference in Geneva, called Europe-Africa Summit hosted by the former prime minister of France. Incidentally we were discussing the World Trade Organisation, impact of Africa or lack of it in international trade. It was a very depressing conversation, and that evening after the conversation, I was taking a stroll with a couple of Africans who were in that meeting, one of them was a deputy managing director at IMF, Alhasan Quatara who is now president of Côte d’Ivoire. I asked one of them, why is it that we Africans can’t get our acts together at the WTO. He then said, you know Pat, why don’t you tell your people, when African leaders are coming to this meeting, they don’t do their homework; they go shopping, what others draft they sign. I had this in my head and was thinking of it when I ran into my classmate who asked me “what happened to Nigeria?” I walked down the hall and ran into Senas Ukpang who served in Babangida’s regime, I said where you dey go, he said I am going to WTO. So I said what’s our game plan, he said o boy if we reach there anything we see we go sign. I came back to Lagos thoroughly depressed. This is how my future was stolen.

In 1993, some of us said no! We’ve got to change things. Then we took to Abiola as a part to new sanity. We mobilized, voted, counted the votes knew the outcome, called around and also got the results and we knew that Abiola had won the election. Two days later I got on the plane, to go to a religious convention in United States. I was on the floor of the Marriott in Boston when a Ugandan who was attending the convention came to me and said you Nigerians, whenever Africa gets ready to make progress, you set us back. I asked him, what he is talking about. That’s how I learnt that the election has been annulled. So I just withdrew from the convention floor went up to my room, and began writing. One of the problems I have is that whenever anything upsets me, I begin to write about it. That created a second problem. The piece I wrote that day was titled “We Must Say Never Again”. Those days, there was no email, so I faxed it to The Guardian.

While I was still out in the US, they published the article. In that article, I challenged professionals and educated people who don’t pay enough attention to these things, thinking they can just survive in the comfort zones of their lives. They replied asking what do we do. By the time I returned to Nigeria, I started writing another article titled “On a Road Map to What We Can Do.”

The struggle over June 12 was again a defining moment in my life. We were beaten in the streets of Lagos by Police men who were brought from some parts of the country to stop us from protesting. I remember a story in the Vanguard, a day after, about my missing glasses. But that’s what you do for your country. We went through that, some of us refused to give up, while some withdrew. In the end, the army had had enough. Abdusalami Abubakar beat a retreat, and we had to make a decision.

A meeting was summoned in my office in Idowu Tailor, Victoria Island in 1998. People like the now late Waziri Muhammed, thought we should transform the group into a political movement, and seek power to affect those changes that we were calling for. There were some who thought that we were professionals and had done our civil duty as citizens, and should allow politicians to come into place and continue. After the meeting, we were standing in front of my office and Donald Duke said to me “look, you guys have decided but me, I am going back to Calabar to go and organise.” I have still held myself personally accountable for that historic error because my vote went with those who said we’re professionals and let’s go back to work. Unfortunately, the politicians were not even ready. They did not trust the military, they did not think the military was really a problem, and because nature abhors a vacuum, the soldiers who now changed uniforms and their bad men moved in and took over the space and till today Nigeria has not recovered from that error.

Please Watch Here:

Talking about politics, you are currently leading a group known as the third force which is poised to ensure that the right leaders are chosen in 2023, can you throw light on the journey so far?

Like I was saying, by 2003, it was clear that we had made a major error, because when these characters then went into politics, to make matters worse, oil prices which were down to $9 under Abacha suddenly went to the stratosphere, reaching 140 at some point. As the money became available, these characters privatized the common wealth and used money to erect a barrier of entry into politics. You cannot save Nigeria until you remove money from the political system, that’s clear now.

The fight for 2023 must be on how to end the influence of money in politics. If it does not end, Nigeria will continue to be prostrate, and shame of the black man.

By 2003 we began to say, look, we have made a grave mistake, maybe we should have gone with what Donald Duke and co suggested in 1998. How can we change this? My first strategic move was to begin to try and put together well-meaning Nigerians across board from various backgrounds. A number of people tried to encourage us to support politicians who were going in so that they can do the right thing. I was pulled into some directions. One direction was to help presidential candidate, Olusegun Obasanjo who had called a meeting, a big launch of who is who in Nigeria to mark the Independence Day anniversary. The event took place in Ota Ogun State in 1998 at Gateway Hotel. There was the usual token representation, which included Olisa Agbakoba, Clement Nwankwo, myself and others. We sat together at the launch. General Obasanjo came and pulled a chair and sat with us, and said ‘I made a terrible mistake in 1979. I should have just brought people like you together and hand this country over to.’ I thought wow! Light is coming to this man!’

So when some mutual friends then suggested that General Obasanjo wanted a couple of advisors as a presidential candidate, I didn’t hesitate to make myself available, because I was bent, literally everyday on policy issues. That’s how we started, sometimes we fight over issues. But I like his disposition because he is capable of learning. Sometimes you fight with him over an issue and the next day you discover that he has changed his position. One of my favorite examples is privatisation. Today, General Obasanjo carries himself like he invented privatisation but I know how much he and I fought on the subject before he changed his mind and accepted. Anyway, it’s good, that’s what learning is all about.

At some point in time I actually got tired of fighting.

By 2003 when I saw that the whole thing was really a mess, and that we should do something, my first inclination was to gather those of our friends who had greater vision of how things was going to be, and then offered themselves to run, and won like Donald Duke, that we should pool together brain power, International networks, and all of those; all of us come together and take their states as an example and make it an exemplar for everybody else. So I wanted a retreat of people across the spectrum; take a couple of right civil servants, assistant deputy director level, number of military officers, because we also wanted to discourage the army from wanting to be the solution. Take a number of political actors like Donald and co.

I drew up the list, including civil society organisations. And we all went for a four-day retreat on how to remake Nigeria. I had procured the support of a former Ugandan foreign minister called Olara Otunu. At one of those meetings in France, looking at Africa, Olara Otunu impressed me remarkably. He was then an under-secretary general of the UN when Europeans where carrying on that now South Africa is free, it would provide leadership for Africa. When the discussion was going on, how South Africa can show us the way and the light, as Apartheid has just been brought to an end, Olara stood up and said you guys can carry on, on your self deceit as much as you like. Wherever Nigeria goes, goes Africa. If you want to fix Africa, fix Nigeria. So I approached Olara and said to him I would like you to come and talk to us at this retreat. He was very agreeable and I started planning the retreat, I used my money to even book up 72 rooms and all of that. One day, I was in Abuja, I got a call from Waziri Muhammed who said, hey this thing you’ve been planning we’ve got a chance to get it on the easy. I said how? He said Southern Governors are meeting in Lagos, why don’t you fly and come back to Lagos, immediately. We can get a number of them to come to this meeting in Aliko Dangote’s house tonight. We can then have young business men leading young politicians during the first brainstorming before we go to that your retreat. So I said it sounds interesting. I didn’t go back to my hotel, I went straight from where I was to the airport to catch a flight to Lagos. Then we met in Aliko’s place at night. Donald Duke chaired the meeting. At some point of the meeting, I realised it was a big mistake. Had I just focused on what I was just going to do and not allow Waziri’s quick reaction thing to come in, we may have probably travelled a different track, but what’s done is done.

They eventually converted the movement and called it under 50s movement. It has nothing to do with age. My original idea was that all of us would come together and take Donald Duke, take Adamu who was then governing Bauchi; take like three or four of them, give everything we had, our global contacts, our know-how on policy, and make those states as exemplar states, so that people would know that good government matters. In the end we said, okay, let us even run. So as concerned professionals, we created something we called the Restoration Group, and then join forces with Okey Nwosu who had just registered in ADC. That’s how I became a presidential candidate of ADC in 2007. But of cause history properly documented that no election took place anywhere in Nigeria in 2007.

Today we get to a situation where we are facing tragedy in the face. These guys have not really wasted my life but lives of millions of people and mine was only dented. Other lives were completely ruined. In this closing chapter of the book of my life, I ask myself, what are the options before me. I can raise a white flag and move to some small towns ivy league school campus in America and live happily or can actually start a guerrilla war and die in the field, probably more noble life than this nonsense that we’re going through. Or I can help the next generation awaken to the fact that we have sold them short and help prepare them to rebuild the country. I kept struggling for light on what is really the ideal thing to do. I started this Centre for Values in Leadership (CVL) in 2004 precisely to help the next generation understand that what we have is not leadership, and that there is a part to leadership which is essentially self sacrifice for advancement of the common good, the good of others. Because once you focus on yourself, you are not a leader. Leadership is about ‘others-centred behaviour’ not about ourselves.

I realised very sadly that even corporate Nigeria has not been ready to support this. The people who have made money in Nigeria, either because they are short-sighted or think doing things right would take a way from them how they made money. I struggle to run this place. I use what I earn from different sources to run it. I work like a donkey, but I barely manage to do the needful in many areas, because whatever I earn, I try and use to support causes that somehow advance the good people in the society.

The last tranche in the political front on the various efforts to try and make it better is when I said let’s try and create a movement. That would bring together civil society and the disinherited Nigerians, the women, youth, professionals and the intellectuals. A group of people have captured the Nigerian state and there driving concept is exclusion, so that in excluding, they can just chop it all. It doesn’t matter if every body else dies. I look at Lebanon, and I see what people like them have done to Lebanon, Paris of the Middle East, now a completely failed state. And I look at people who run Nigeria and know that they are cousins of these guys in Lebanon, literally, figuratively, and in some cases even physically. I said to myself, we must not let Lebanon’s Lords, Venezuelas, be that of Nigeria. This is the purpose of the effort that we are making; to bring these various movements together. There are several movements. Some focusing on leadership, some focusing on policy, others focusing on a variety of things. Bring them together with a group of political parties to create something that can bring a Nigeria redemption. This is what we are trying to do as our last way before we die.

There is this conversation that it’s the turn of the Southeast to produce the president. If you’re asked to contest, would you accept it?

I continue to say that what Nigeria needs is a competent Nigerian. If in trying to be representative, some part of Nigeria have been left out in the leadership thing. There is somebody who is a good Nigerian, who happens to come from that part, common sense suggest why not that person.

I have said that Instead of any of these kangaroo characters, mercantile fellows who run around the Southeast as politicians and aiming to be president of Nigeria, please I would give it to Dukpe Umaru or anybody. That is my position.

Should I be asked by may be well-meaning people, Nigerians, who are gathered from Southeast, South-south, northeast, Northwest, to move in that role as a good Nigerian, I have a moral obligation to respond to that. They would look at what is readily available and what is possible, and we must not give up on Nigeria and how to make that happen.

Looking at Nigeria’s economy today, what is your take on the deficit in 2022 budget, is it sustainable?

Of cause it’s not sustainable. People read economics upside down many times. They will give you deficit ratios from some part of the world that others have considered as sustainable, but those guys know they are producing. They know they can project where the production will lead them to. The ultimate deficit country is America, but it’s the ultimate production machine. So, to say America has this deficit and so our own is not so bad show you are mental, you don’t understand economics. America can afford that deficit, but we cannot. Even America gets hurt by that deficit but they can afford it because their production machine would rev up.

Ours is not sustainable. Now, if you look at what is even more troubling. Those days when you talk about IMF conditionalities, we want to borrow, and borrow, oh things are difficult! Have you watched the behaviour of Nigerian politicians, is there any suggestions that they are ready to do anything like tightening belt. I won’t trust people who behave like that with borrowed money. They would just squash the future of people who would pay back that debt. We have made this mistake again and again.

Again, I said this as part of my continued fighting with then President Obasanjo, despite the fact that I have a lot of regards for what he has done in many areas. Here is President Obasanjo with a swaga paid off Nigeria’s debts. I was depressed. It’s nice to be debt-free. If we had reached Naples terms agreement, it would have enabled us pay off that debt quietly and without any problem for sustainable on those arrangements, and we could have taken the kind of cash flow that was coming in, provide this as counterpart funding for what is going to be significantly private capital to create markets and trigger off what is today typically referred to as the prosperity paradox of private capital, building infrastructure that would drive sustainable growth.

What is your take on the fuel subsidy controversy, should the government remove the subsidy or keep spending to reduce the cost for Nigerians?

These are very nuanced conversation. Not as simple as remove, take, don’t remove. If you remove this subsidy -by the way subsidies don’t make sense you are just shortchanging yourself. But if you remove them with kind of politicians that I have just described, who will just see new cash to spend, you would probably do more damage than anything else.

I have said repeatedly that when you are a lame duck government, when your time us about to expire and you may be suspected to have ambition of taking some monies away before you go, you usually make very few decisions. I have seen lame duck governments around the world, but I have never seen one worse than the present one in Nigeria. Buhari’s government became a lame duck two and half years ahead if his time because of the way they have managed the country. And so there is no trust for it, there is a huge trust deficit between the Nigerian people and the government. To make that kind of policy decision, is crazy because people can’t trust them to use those resources well. And to then go and borrow in the stead of that removal is even doubly dangerous. This is the dilemma of where Nigeria is. So what we rightly need now is a government of national unity that will determine how country would function because Buhari’s government has actually ran out of legitimacy on the one hand there is much time still left. How we would do it I don’t know.

Some are saying that before the government remove subsidy they should put some conditions in place like revitalizing the existing refineries and setting up modular ones to boost local production of petrol, how do you see that?

How are they going to do that? You see, Nigeria’s import list is dominated right now by the two things Nigeria should be exporting right now: petrol and food. How can a country there. You can’t produce food because there is so much violence, people can’t go to their farms. We can’t export petrol which we should have been exporting from 30 years ago, but to import it so so that our friends can play games and make a lot of money from selling petrol. Nigeria’s history would be hard to write.

As chairman editorial board of Prime Business Africa, how do you feel heading the editorial, what is your assessment of the online publication so far?

So far, very very well. Clearly Nigeria was in need of what your organisation has come to provide, but the scope needs to be broadened. The kind of information that small business people need to make choices for investment and growth needs to get to them because that’s where Nigerians need to exploit most. Strengthen those small entrepreneurs to build a people’s capitalism. I wish you all well as you work.

Follow Us