COVID-19 pandemic disruption coupled with crisis in some parts of the world had led to periods of lost learning but the solution was found in “Accelerated Learning Programme” an approach pioneered in some African countries including Northern Nigeria, over the past decade to enable out-of-school children gain access to education or to catch up on missed study sessions.

A research foundation, Education.org, conducted studies into the initiative which was adopted in several African countries and found that such an education system had impressive results and when adapted to scale up learning in affected areas could help Sub-Saharan African countries save up to $18 billion of the estimated GDP loss due to pandemic crisis.

Join our WhatsApp ChannelIn this interview with Prime Business Africa’s VICTOR EZEJA, Dr Randa Grob-Zakhary, Founder and CEO of Education.org speaks on how the organisation’s research led to the launch of an evidence-based guide for governments, policy makers and education leaders, highlighting how they can adapt such system to mitigate the impact of lost learning caused by COVID.

1. Could you briefly describe the thrust of your research on evidence-based accelerated learning?

Accelerated learning is an approach that’s been pioneered across Africa over the past decade to get out-of-school kids into education. It involves compressing up to three years of primary education into one school year. They do this by focusing on the basics of literacy and numeracy, taking a child-centred and interactive approach to learning, and actively engaging communities in support of their children’s education.

READ ALSO: Africa can recoup over half of pandemic GDP losses by using evidence-based ‘accelerated learning’ to help children catch up

The approach has had impressive results in several African countries. We wanted to gather and analyze all the evidence and then use it to produce guidance for government policy makers as we felt it had many valuable lessons for planning their post-COVID catch-up education.

We took a deeper look at the experiences of eight African countries – Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, South Sudan and Uganda – how they’ve adapted accelerated learning to their particular situations – to the conflict zone of northeast Nigeria, post-conflict societies in Liberia and Sierra Leone, refugees in Kenya and Uganda, or children marginalised by extreme poverty in Ghana and Ethiopia.

We produced a High-level Policy Guidance Document for education leaders which is really a decision-making tool for policy-makers and their technical teams. We also published the Accelerated Education Programme Evidence Synthesis, a rapid global synthesis of crowd-sourced evidence, much of it unpublished, amplifying and elevating previous accelerated education work and uncovering evidence that needs greater visibility.

2. How can countries with high records of out-of-school children due to economic crisis, insecurity, conflicts, etc., adopt these guidelines for accelerated learning, especially for the younger ones?

Our guidance provides experiences and examples from countries that have effective accelerated programmes in resource-poor contexts and conflict-affected settings, showing how it is possible to meet the learning needs of marginalised children in adverse conditions.

The policy guidance document makes it clear that one size does not fit all when it comes to embarking on accelerated education programmes. It’s important to analyse the local context and draw on evidence that has most relevance to your situation and specific challenges.

We offer governments guidance on how to assess their needs and readiness for adopting accelerated education principles. We help countries reflect, depending on where they are today, on the best place to invest time, energy and resources based on the most effective features of accelerated education programmes.

3. How many countries within Africa has your organisation researched or engaged with on the adoption of accelerated education programmes?

Education.org conducted peer-reviewed analysis and synthesised evidence from around the globe but we took a deeper look at accelerated learning experiences in eight African countries: Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, South Sudan and Uganda.

We reviewed the evidence on accelerated education programmes and analysed policies in these countries. The majority of these sources were previously unpublished. We created an Evidence Synthesis for policymakers that offers deeper insights into accelerated education practices and actionable guidance from these countries. You can read case studies on some of these countries on our website: www.education.org/accelerated-learning

4. What has been the experience of adopting accelerated education in these countries, and have there been successes?

Yes, the evidence shows us that accelerated education can be adapted to many different challenging contexts. Ethiopia’s Speed Schools, for example, have pioneered the approach for a decade now for out-of-school kids affected by extreme poverty, such as those required working to support their families. The Speed Schools – dedicated accelerated classrooms in existing schools – have supported more than 250,000 9 –14-year-old persons in basic literacy and numeracy, with 95 per cent of them transitioning into formal schooling. In fact, these students achieve higher-than-average results compared to their peers when they transition. The classes have been so successful such that the government has adopted them into the formal school system with a dedicated ‘Speed Schools Unit’ to scale the model, and now funds 75 per cent of Speed School classes.

Another strong example is in Liberia where accelerated education programmes have adapted to the post-war and post-Ebola context. The Luminos ‘Second Chance’ programme there has brought over 12,000 kids into education, transitioning 90 per cent into government schools. It highlights the importance of a strong focus on social and emotional learning in settings where children have lived through great trauma.

What comes through from the evidence we’ve analysed is how accelerated education programmes must have a proactive focus on the most vulnerable young people – such as working children, adolescent girls, especially those affected by teen pregnancy, or refugees. They work because they are flexible, proactively adapting to the needs of these children.

5. What education levels does your guide on accelerated learning cover?

Primary education is the focus of the greatest number of programmes, but there are accelerated education programmes for secondary education too. In South Sudan, for example, they’ve started using accelerated education with teachers, helping them to get their secondary certificate so they can progress with teacher training. The designs of these programmes vary but a key ingredient of success is that they align with the national curriculum and are certified by government.

6. Are there measures in the guide for accelerated education in places that have over time recorded poor enrolment due to extremist religious ideology that opposes the adoption of Western education? What guidelines do you recommend for this context?

Yes, one of the programmes we’ve looked at was in Northeast Nigeria where, as you know, conflict has disrupted education very seriously with many communities having to flee from their homes. Girls have been particularly marginalised.

The USAID-funded Addressing Education in Northeast Nigeria (AENN) programme was effective in addressing these challenges head-on by working with communities to get more girls into class and provide training on conflict-sensitive education practices with teachers. They also set up dedicated learning centres just for girls. By the final year of the programme, 59 per cent of the enrolled students were girls, despite the opposition hindering girls’ education in the region.

7. Your research indicates that Africa could recover up to US$18 billion a year if leaders apply the best accelerated education interventions to recover lost learning and reach children who were out of school even before the pandemic. Could you expand on how this GDP recovery can be achieved through the AEP model?

Lost learning carries a heavy economic cost to young people’s future earnings and to their national economy in terms of lower contributions to GDP.

Education.org sought to quantify just how much economic gain might be recovered from the McKinsey estimates of pandemic-related GDP losses if the most effective strategies for accelerated and catch-up learning were applied.

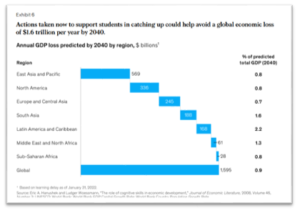

McKinsey analysed UNESCO data on COVID-19 related school closures and World Bank data on “mitigation effectiveness” (e.g., quality online learning) to estimate the number of months of learning lost between February 2020 and January 2022. The average student globally lost about eight months of learning (with significant variations by region). By 2040, when the current cohort of school children will have joined the labour market, the lost learning amounts to a predicted global GDP loss of $1.6 trillion dollars per annum1.

A year of accelerated learning can cover up to three years of normally-paced learning, cutting the length of instruction by two-thirds – with the potential to be applied for even shorter periods of instruction – according to the best available evidence around accelerated education 3,4.

If accelerated learning could be adapted for and extended to all students globally, and two-thirds of the time spent out of school due to pandemic school closures could be recovered, the global economy would benefit by $1 trillion dollars per annum by 2040 (when most of today’s K-12 students will have entered the workforce). Accordingly, each region stands to recover 66 per cent of the projected lost GDP shown above. Using this approach, Sub-Saharan Africa could recover up to $18B, over half of its predicted GDP loss of $28 billion.

Follow Us