The Nigerian Senate’s decision to reconvene for an emergency plenary session today 10 February is more than a routine legislative adjustment. It is a clear signal that the controversy surrounding the Electoral Act amendment has struck a nerve, shaking public confidence and igniting nationwide scrutiny.

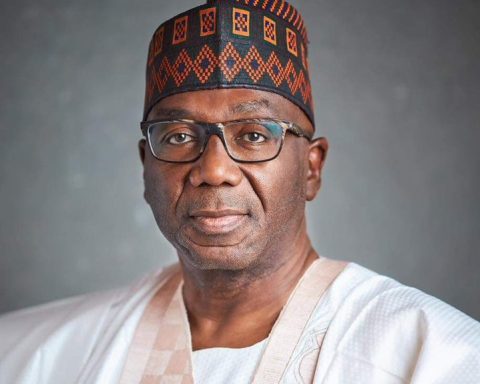

The official notice, signed by the Senate Clerk on the directive of Senate President Godswill Akpabio, offered no explanation for the urgency. Yet the timing, coming amid swelling backlash over the amendment, strongly suggests lawmakers are responding to mounting public pressure.

Public discontent has intensified in unmistakable ways. The protest staged at the National Assembly yesterday further reflects a citizenry unwilling to remain silent over what it sees as a weakening of electoral safeguards. It is also evidence that Nigerian youths do not protest only on social media, contrary to the long held notion that their activism rarely moves beyond online spaces.

Join our WhatsApp ChannelThe agitation has widened, drawing in the 2023 presidential candidate of the Labour Party, Peter Obi, (now in ADC) alongside civic groups demanding that lawmakers revisit provisions perceived as undermining transparency. At the centre of the outrage lies the Senate’s retention of Section 60(3) of the Electoral Act, which permits electronic transmission of results without making it mandatory, a distinction many Nigerians see as preserving loopholes rather than closing them.

READ ALSO: Voting in the Dark: Nigeria’s Electoral Reform Fails to Shine

Therefore , today’s (February 10) emergency sitting therefore carries weight far beyond parliamentary procedure. It is a moment of reckoning for the National Assembly, one that will test whether lawmakers prioritise institutional credibility and public trust or retreat into legislative convenience. The deliberations will inevitably expose whether Clause 60 was allowed to stand by design or whether there remains genuine willingness to align reform with the democratic expectations of Nigerians.

Why are Nigerians Protesting

Since 1999, Nigeria has amended the Electoral Act multiple times, yet the law has consistently failed to empower the electorate to freely and transparently choose their leaders. Practices such as ballot box snatching, manipulation of results, and tallying votes beyond the number of accredited voters have remained recurrent.

In 2023, these challenges persisted despite the deployment of BVAS devices intended to modernise voting and enable real-time transmission of results. Many election officers were unable to upload results immediately from polling units to INEC’s portal.

The legal framework was partly to blame. Section 60(3) of the 2022 Electoral Act, which the Senate retained in its current version, stipulates that “The electoral officer shall transfer the results, including the number of accredited voters and the results of the ballot in a manner as prescribed by the Commission.” In practice, this provision left room for interpretation, allowing reported “technical glitches” to subvert the real-time transmission of results. Consequently, the outcome of the 2023 presidential election was widely perceived as manipulated, fuelling claims that the public will had been compromised.

This situation prompted opponents, including Mr Obi and Mr Atiku Abubakar, to challenge the outcome in court, presenting evidence they said showed widespread mutilation of election result sheets. Much of this material had already begun circulating online during the election, with many citizens tagging it as proof that the process had been rigged, further intensifying public suspicion and debate.

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court in it’s post election judgement clarified that the Independent National Electoral Commission’s Results Viewing Portal(IReV)cannot be considered part of the official collation system unless expressly entrenched in law.

The adoption of electronic transmission, the court emphasised, must be explicitly stipulated in the Electoral Act to be legally binding. It was this legal and procedural gap that prompted the current amendment. The reform was then necessary if Nigeria genuinely seeks a credible, transparent, and modern democratic process.

Although, public attention has largely focused on the Senate’s decision to leave electronic transmission of results non-mandatory. Yet the amendment covers several other areas with significant implications for electoral integrity.

Clause 60 retains the 2022 provision allowing results to be transmitted to the collation centre, rather than mandating real-time uploads to the INEC Results Viewing Portal.

Clause 47 preserves the Permanent Voter Card as the sole mandatory form of voter identification, with BVAS replacing smart card readers for accreditation.

Clause 22 increases fines for illegal sale or use of PVCs from N2 million to N5 million while retaining a two-year jail term, and separately imposes stiffer penalties for vote buying, raising fines from N500,000 to N5 million.

Clause 29 shortens the deadline for political parties to submit candidate lists, Clause 44 retains procedures for ballot paper inspection, and Clause 136 reforms post-election disputes by mandating reruns where a candidate is disqualified instead of automatically declaring the second-place candidate the winner.

The public outrage over the Electoral Act amendment is understandable. The reform fails to address the very issues highlighted by the Supreme Court and retains Section 60 of the 2022 Act, leaving the question: if real-time electronic uploads cannot be enforced, what was the purpose of the amendment in the first place?

Clause 22 also raises serious concerns. Reducing the 10 years recommend the jail terms and relying primarily on fines for offences such as vote buying and manipulation of PVCs appears convenient for politicians. Can a presidential candidate or a governor, who can afford the enormous costs of running for office, not pay a fine of N5 million? Such offences should carry non-negotiable penalties, as vote buying has been a major persistent problem in Nigeria democratic growth.

Taken together, Clauses 22 and 60 illustrate where amendments could have genuinely strengthened democracy, yet the Senate has failed to act in the public interest.

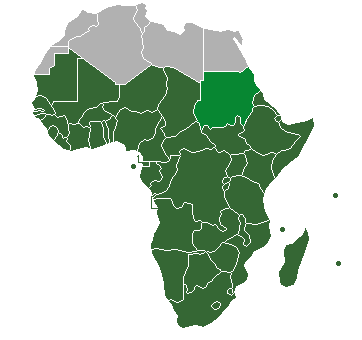

While the Senate President Akpabio, and the majority lawmakers, most from the APC now controlling about 77 seats in the Senate and 205 in the House, (as a result of strategic defections) , cite network issues as the reason for retaining Clause 60, but this argument is unconvincing.

If network reliability is truly the obstacle, who is to be blamed? Why has Nigeria not resolved this problem decades after independence?

The controv and network excuse rather, exposes a deeper reality. Even if the Senate, had made electronic transmission compulsory, network limitations remain a major obstacle.

Nigeria has about 176,846 polling units, most in rural and remote areas with weak internet and unstable electricity. Only a fraction in urban centres could reliably transmit results immediately.

Urban centres often have stable networks, but many polling units lack coverage entirely. This is not just a technological issue, it reflects decades of government neglect in providing basic infrastructure, which now undermines democracy and benefits politicians. So, Network reliability and providers cannot be solely faulted.

In urban contexts, systems like JAMB exams often run smoothly across centres, showing that connectivity works where infrastructure exists. The problem is the absence of internet and electricity in most polling units in rural communities.

This weak infrastructure, combined with selective lawmaking, fuels public distrust and disenfranchisement, as citizens increasingly feel that leaders are effectively chosen in advance, since the government continues to control INEC, an institution meant to be independent. Many therefore see little point in casting their votes, further eroding participation and accountability.

Lawmakers must align legislation with democratic principles, ensuring that the electorate has the tools and legal guarantees to freely and transparently choose their leaders.

At the same time, infrastructure development, particularly nationwide network coverage and reliable electricity, must be prioritised.

True electoral reform requires more than legal adjustments. It demands a coordinated approach to governance and development, where the state provides the basic services that enable democracy to function. Until these gaps are addressed, reforms will remain symbolic, and public trust in the democratic process will continue to erode.

Yet today’s plenary session will serve as a true test of the National Assembly’s commitment to the voices of its citizens and its willingness to uphold democratic principles.